EEK, A DINOSAUR IN MY COMPOST PILE!

A Creature Not Really So Strange

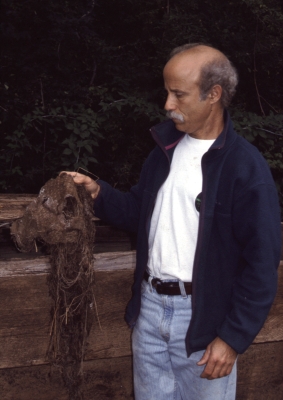

One of the strangest creatures I ever found in my compost was the dinosaur that emerged today as I turned the pile. It was worse for the wear, the gash in its head probably from my machete, the “solar powered” shredder I use for stemmy compostables like corn stalks. (Think about it.) After a year in the pile’s innards, the dinosaur’s greenish, scaly skin has been bleached almost white.

I typically build compost piles through summer and into fall, then turn them the following spring. Turning, not absolutely necessary, lets me mark the piles progress and, as needed, fluff it up for aeration or sprinkle it if too dry. Many people use fencing to enclose a compost pile, which is effective as an enclosure but exposes the pile to too much drying air. My bins, made from artificial wood decking, stacked edgewise and notched together like Lincoln Logs, have solid walls which helps hold in some heat and moisture.

I should mention, at this point, that the dinosaur might, in fact be a lizard. Oh, and something else: It’s made of a rubbery plastic. This ‘saur was unearthed many years ago as I was digging up a mulberry tree. Once salvaged, it resided in one of my garden beds, where it startled people (including me, occasionally) despite its mere foot-long length. It must have hitchhiked along to the compost pile with some garden debris at the end of the season.

Good Feedstuffs Make Good Compost

Just about everything goes into the compost piles: weedy hay, garden debris, kitchen scraps, horse manure, old cotton or wool clothes, weeds, and anything else that is or was living, that is, organic. Also, some dolomitic limestone, which is rock so never was living but is “organic” in the cultural and legal sense. Dolomitic limestone adds calcium and magnesium to the finished mix, increases the alkalinity of the finished compost (to offset the naturally increasing acidity of soils here in the humid northeast), and improves its texture.

The other ingredients offer a spectrum of macro- and micronutrients to the finished compost. Carbon and nitrogen are the two feedstuffs that composting microorganisms need in greatest amounts. I don’t dwell too heavily on the ideal 15 to 1 ratio of carbon to nitrogen for a balanced feed that gets the pile heating and the compost finishing up quickly. Much depends on the size of the feedstuffs and the presence of other natural chemicals, such as natural lignins in wood shavings that slow down its decomposition irrespective of carbon to nitrogen ratios.

I do pay attention to what I put in the piles, using a thermometer, my nose, and my eyes to monitor progress. No heat, bad smells, and slow progress indicate, respectively, too much or too little moisture or too little nitrogen, too much water or nitrogen, and too much or too little moisture or too little nitrogen. It’s all good though. Adjustments can be made when turning a pile, or do nothing and wait longer. Any pile of organic materials eventually becomes compost.

Real Reptiles in the Pile

Other strange denizens, living denizens this time, of my compost piles have been black rat snakes. A few years back, I’d bump into them slithering out of the compost pile as well as coiled into the branches of a blueberry bush and, unfortunately, coming out of the chicken house, two swollen lumps in their bodies evidence of a recent two-egg meal. All-in-all the snakes are welcome for their meals of mice and rats.

I’d also come upon clusters of the snakes’ soft-shelled eggs, up to two dozen or more, as I turned the compost. After incubation in a terrarium, out slid not-very-cute baby snakes.

Decisions, Decisions

Turning compost piles provides relatively mindless relief from more thoughtful gardening such as planting decisions. Where to plant, for example, a dwarf shipova tree, an Alderman plum, and a Concorde pear? And should I risk planting out the borderline hardy Flying Dragon hardy orange (Poncirus, now named Citrus, trifoliata)?

Easier to place are the vegetables, which need to be rotated every year, never (well, almost never) grown in the same location more than once every three years. Rotation prevents overwintering, nonmobile pests from having something to attack close at hand. The vegetable garden is in two banks of beds, so I just move what’s planted in each bed two beds counterclockwise each year, two beds to get them further away from previous years location than would a one bed rotation.

Still, lettuce transplants, extra onions to be harvested as scallions, radishes, and short rows of arugula get spotted in willy nilly.

Heady Stuff, Here

May 5th: This calm, warm morning the whole yard is awash in the sweet, spicy scent wafting from yellow trumpets of clove currant (Ribes odoratum) flowers. In August, this deer, drought, cold, heat, and pest resistant plant will be covered with large, black sweet-tart currants.