LESS SALT IS BETTER

What Does “Salt” Really Mean?

A few years back, one of my neighbors planted a hemlock hedge along the road in front of their house as a screen from the road. Sad to say, the future does not bode well for this planting. The hemlocks very likely will be damaged by road salt. And the prognosis is similar for those stately sugar maples that line so many streets.  Chemically, road salt — at least the more traditional “road salt” — is the same as the stuff in your salt shaker, sodium chloride. Either sodium or chloride ions can be toxic to plants. Chlorine is a nutrient needed by plants, but it is classed as a micronutrient, needed in minute quantities. Too much is toxic. Sodium is not at all needed by plants.

Chemically, road salt — at least the more traditional “road salt” — is the same as the stuff in your salt shaker, sodium chloride. Either sodium or chloride ions can be toxic to plants. Chlorine is a nutrient needed by plants, but it is classed as a micronutrient, needed in minute quantities. Too much is toxic. Sodium is not at all needed by plants.

In a broader sense, a “salt” is any ionic molecule, that is, a molecule of two or more atoms in which electrons, which are negatively charged, are donated from one atom to another. Who gets what depends on how easily an atom or atoms can lose one or more electrons and how hungry another atom or atoms is for those electrons. That ability to donate or be hungry for an electron depends on the number of positively charged protons in an atoms nucleus and the number and arrangement of electrons around the nucleus.

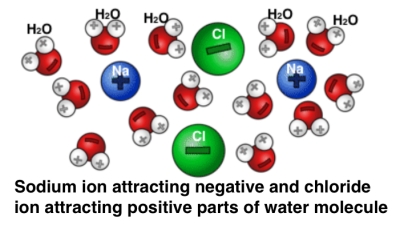

In the case of table salt, the sodium easily loses one electron and the chloride atom is hungry for it. The once neutral sodium atom becomes, after losing an electron, a positively charged sodium ion. The once neutral chloride atom, after gaining an electron, becomes a negatively charged chloride ion. And bingo, these two oppositely charged ions are strongly attracted to each other; they bond. What happens when water enters the picture? A water molecule, because of its shape has a slightly imbalanced charge distribution. The negatively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the sodium ion of table salt, and the positively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the chloride ion.

What happens when water enters the picture? A water molecule, because of its shape has a slightly imbalanced charge distribution. The negatively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the sodium ion of table salt, and the positively charged side of the water molecule gets attracted to the chloride ion.

Salt Problem in Winter, and Beyond

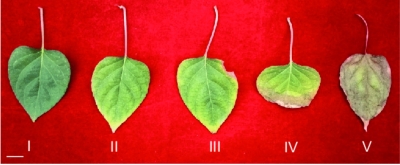

Any salt (ionic molecule), not only sodium chloride, attracts water so will simulate drought if in excessive amounts in the soil in the same way that potato chips dry out your lips. This leads to common symptoms of salt injury. First evidence of salt injury is browning of leaves, starting along the leaf margins. Early fall coloration and defoliation also can occur. More severe injury is manifest by twig or branch dieback, or death of a whole plant.

Progressive symptoms of salt damage

Salt also has an adverse effect on the soil itself, which is particularly insidious since it’s not as obvious as a dead plant. Over a period of time, sodium in salt can pull soil particles together, squeezing air out of the soil. As a result, roots suffocate.

Plants suffer most from salt in dry soils, so any plant exposed to salt in winter will benefit from mulching and watering during summer droughts. Watering also leaches sodium out of the soil, which improves soil porosity. Gypsum further aids in fluffing up a soil made too compact by sodium, by displacing sodium in the soil with calcium.

Honeylocust

Plants vary in their tolerance to salt. In addition to hemlock and sugar maple, the following trees and shrubs should not be planted where they will be exposed to salt: red maple, American hornbeam, shagbark hickory, dogwoods, winged euonymus, black walnut, privet, Douglas fir, white pine, crabapples, beech. Plants with a moderate tolerance to salt include: Amur maple, silver maple, boxelder, red or white cedar, lilac. Deciduous plants with high tolerances for salt include: Norway maple, paper and grey birches, Russian olive, honeylocust, white or red oaks, black locust, and many of the poplars and aspens.

For my neighbors who wanted an evergreen hedge, better choices would have been: white spruce, Colorado blue spruce, or Austrian pine. Perhaps even yew, since the site was somewhat shaded.

Mitigation or Avoidance

An obvious way to limit problems with road salt on plants, even salt that you might spread on your driveway or paths, is to use less salt, or none at all. (After once slipping on ice in my driveway and suffering a slight concussion, I became very aware of weighing damage to plants against damage to humans.) Fortunately, there are ways to keep all creatures happy.

Traction on ice or snow can be increased by spreading sand or sawdust.

A very effective technique, one that uses less salt, used by some road crews is to spray a salt solution on dry roads before a weather event that will bring slippery conditions.

When salt must be used, use a minimum amount or substitute a salt other than sodium chloride. Calcium chloride, for instance, is a salt that is only a tenth as toxic to plants as sodium chloride. One of the best materials as far as effectiveness with minimum damage to vehicles, concrete, and vegetation, is calcium magnesium acetate (CMA); but it’s expensive.

Salts that are fertilizers, such as ammonium nitrate or calcium nitrate, melt ice and at the same time nourish plants. Salts other than sodium chloride still need to be used with caution, for they can cause salt desiccation and/or nutrient imbalances in plants. My favorite treatment for icy conditions here at home is spreading wood ash. Effectiveness comes from the dark color absorbing sunlight to speed melting, a slight grittiness increasing traction, and its salt content. Of course, access to wood ash means you or an ash-rich friend burns wood for heat.

My favorite treatment for icy conditions here at home is spreading wood ash. Effectiveness comes from the dark color absorbing sunlight to speed melting, a slight grittiness increasing traction, and its salt content. Of course, access to wood ash means you or an ash-rich friend burns wood for heat.

For all its benefits, wood ash is a mess if tracked indoors. I take off my shoes or boots in the mudroom.