AN ICEY BEGINNING, WITH KIWIS

Pruning Weather

Yesterday was a fine day for pruning, windless with a sunny sky and a temperature of 19 degrees Fahrenheit. The ice storm had turned this part of the world into a crystal palace, with branches clothed in thick, clear sleeves of ice.  From an auspicious vantage point, a pear tree glowed like a subdued holiday tree as hints of sunlight’s reds and blues refracted from the natural prisms on the branches.

From an auspicious vantage point, a pear tree glowed like a subdued holiday tree as hints of sunlight’s reds and blues refracted from the natural prisms on the branches.

Witchhazel flowers

What a pleasant setting for pruning! The usual recommendation is to hold off pruning until after the coldest part of winter, which typically occurs in late January and early February, is over. I’ll admit to rushing outdoors, pruning shears in hand, before that time period, with some plants not long after they dropped their leaves in autumn. That was with plants, such as gooseberries and currants, least likely to be damaged by cold weather.

I was anxious to begin pruning in earnest as an excuse to get outdoors and because I have lots of plants to prune, mostly fruit plants. It all needs to be done before leaves unfurl in spring. And, as spring inches closer, sowing seeds, spreading compost, and other gardening activities increasingly vie for my time.

So I’m out in the crystal palace working on my hardy kiwifruit vines (Actinidia arguta and A. kolomikta). In case you’re unfamiliar with this plant, it’s a dead ringer for the fuzzy, kiwis you see in the markets — except that hardy kiwifruit is grape-size with a smooth, edible skin. The resemblance is even greater beneath the skin — except that hardy kiwis are sweeter and more aromatic. And while a fuzzy kiwi vine will sulk or die back below 10 degrees Fahrenheit, hardy kiwis tolerate winter weather below minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit.

Kiwi Training and Pruning

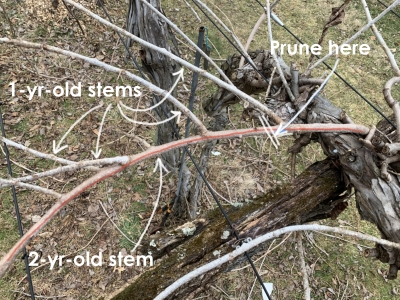

A hardy kiwi vine bears fruits on new, growing shoots originating off one-year-old stems.  The goals in pruning are to keep the plant reined in to a convenient size for easy harvest, to eliminate enough stems so that those that remain bathe in sunlight and air, and to coax growth of new stems off which will emerge, the following year’s fruiting shoots.

The goals in pruning are to keep the plant reined in to a convenient size for easy harvest, to eliminate enough stems so that those that remain bathe in sunlight and air, and to coax growth of new stems off which will emerge, the following year’s fruiting shoots.

Kiwi vine, before pruning

Pruning also removes plenty of one-year-old stems. That cuts down yield but lets the vines pump more goodness into fruits that remain, for better flavor. (Pruning kiwis is described and also diagrammed in my book The Pruning Book.)

Training a kiwi vine to some sort of system keeps the vigorous growth organized. My plants grow on a trellis of metal or locust T-posts spaced 15 feet apart, with 5 wires (actually nylon monofilament) running perpendicular to and spaced out across to the tops of the T’s. Each kiwi trunk runs from ground level up to the middle wire, at which point it bifurcates into two permanent arms, called cordons, running in opposite directions along the middle wire. Fruiting arms grow out perpendicularly to the cordons and the wires, draping themselves over the two outermost wires on either side of the the cordons.

I actually began pruning a couple of weeks ago, starting to disentangle the stems by walking along on either side of the row with my cordless hedge shear, shortening any stems to a few inches beyond the outermost wires. Yesterday I began cutting any two-year-old stem — any stem that fruited last summer — back to its origin or to a one-year-old stem near the its origin. The one-year-old stems, those a little more than pencil thick of moderate vigor, will bear fruiting shoots this year in late summer or fall.

After all this pruning, plenty of one-year-old stems remain, too many for top notch fruit. So I’ll move down the cordons and remove enough one-year-old stems so that none is closer than eight to twelve inches from its neighbor.

Not done yet. In spring, after growth has begun, I’ll clip each one-year-old stem back to about 18 inches.

If you grow grapes, you probably noted that they bear and can be pruned similarly to the kiwis. I even grow some grape vines along the same trellis as the kiwi vines.

The main difference is that grape vines’ one-year-old shoots can be cut back more severely than the kiwi stems. Mine get shortened to a couple of buds each, which is only about three inches, from the cordon; it’s called spur pruning. Everything else is the same.

Ice is Nice, Sometimes

Those sleeves of ice on the kiwis actually made pruning easier. A sharp tug on a cut stem quickly disentangled it and let it slide free from its neighbors.

All this ice did, of course, weigh down branches of large trees which, coupled with strong winds after the storm, sent many limbs plummeting to the ground. Particularly surprising were my birch trees, a tree known for the limberness of its trunk, a characteristic immortalized in Robert Frost’s poem Birches:

I’d like to go by climbing a birch tree,

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more,

But dipped its top and set me down again.

That would be good both going and coming back.

One could do worse than be a swinger of birches.

This storm was more than two of my multi-stemmed birches’ trunks could bear; they cracked. But Mr. Frost was writing about white birches. Mine are river birches.