FRUITS UNLAWFUL AND LAWFUL

Interloper, Not Welcome by Everyone

As I was coming down a hill on a recent hike in the woods, I came upon an open area where the path was lined with clumps of shrubs whose leaves shimmered in the early fall sunshine. The leaves — green on their topsides and hoary underneath — were coming alive as breezes made them first show one side, then the other.

The plants’ beauty was further highlighted by the abundant clusters of pea-size, silver flecked red (rarely, yellow) berries lined up along the stems. I know this plant and, as I always do this time of year, popped some of the berries into my mouth. The timing was right; they were delicious.

Many people hate this plant, which I’m sure a lot of readers recognized from my description as autumn olive (Elaeagnus umbellata). What’s to hate? The plant is considered invasive (and banned) in many states in northeast and midwest U.S. “It threatens native ecosystems by out-competing and displacing native plant species, creating dense shade and interfering with natural plant succession and nutrient cycling.”

But there is a lot to love about this plant, in addition to its beauty. In spring, about the middle of May around here, the plant perfumes the air with a deliciously sweet fragrance. And poor soil is no problem. An actinobacteria (Frankia) at its roots takes nitrogen from the air and converts it into a form that plants can use.

That ability to make its own fertilizer is just one reason this plant was loved before it was hated. Native to Asia (where the plant is not considered invasive), autumn olive was introduced into the U.S. and the U.K. about 200 years

ago for their beauty and to provide shelter and food for birds, deer, bees, racoons, and other wildlife. The plant isn’t stingy with its garnered fertility. The soil near plants becomes richer, all to the benefit of nearby other plant species. As such, autumn olive has been planted to, for instance, reclaim soils of mine tailings, and, as interplants, to spur growth of black walnut plantations (by over 100 percent).

But let’s get back to me — and you — eating the berries. The berries are high in lycopene and other goodies so most sources tout the health and healing benefits, after admitting that the berries are astringent and tart.

But, for most autumn olive plants, that’s only if they’re eaten underripe. Right now around here, some plants are offering their dead ripe berries that are neither tart nor astringent, but sweet. Don’t mind the single seed inside each berry. Just eat them also; they’re soft. That window of good flavor is fleeting, lasting only a couple of weeks.

And eating the berries, seed and all, will slow the plants’ spread, pleasing invasive plant people.

So Bad(?) Yet So Good

Are invasive plants really bad? Or just bad for us? Planet Earth likes plant growth. Plants take in carbon dioxide and release oxygen, sequestering carbon, blanket the ground to limit soil and water erosion, and help support micro and macro communities of organisms.

Natural landscapes and their associated natural communities aren’t static. They change as they evolve. No doubt, humans have altered many natural successions. That might spell disaster for our aesthetic or economic sensibilities, but is not “better” or “worse” for our planet.

Scandinavian Dreams

Noncontroversial is another red berry that I am now picking and enjoying. That’s lingonberries (Vaccinium vitis-idaea). If you are Scandinavian, you probably just smiled and a dreamy look came into your eyes.Each year, thousands and thousands of tons of lingonberries are harvested from the wild through out Scandinavia, destined for sauce, juice, jam, wine, and baked goods. A fair number of these berries are, of course, just popped into appreciative mouths. Most everyone else only knows this fruit as a jam sold by Ikea.

out Scandinavia, destined for sauce, juice, jam, wine, and baked goods. A fair number of these berries are, of course, just popped into appreciative mouths. Most everyone else only knows this fruit as a jam sold by Ikea.

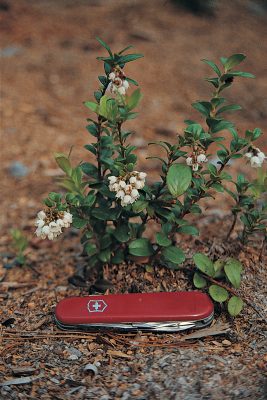

I grow this fruit and am now enjoying the fruits of my labors. I planted it both for its good looks and its good flavor, which got it a chapter in my book Landscaping with Fruit. (Autumn olive also made it in.) Let’s start in spring, when cute, little urn-shaped blossoms dangle singly or in clusters near the ends of the thin, semi-woody stems rising less than a foot high. These urns hang upside down (upside down for an urn, that is) and are white, blushed with pink. They’re not going to stop traffic from the street, but are best appreciated when plants are grown where they can be looked at frequently and up close—such as in the bed at the front of my house.

4-44-P14

If you miss the spring floral show, you get another chance because lingonberries blossom twice each season. This second show, appearing in mid- to late summer on young stems, bore the fruits I am now enjoying.

Lingonberry sports evergreen leaves, the size of mouse ears and having the same green gloss as those of holly. Like holly, they retain their lush, green color right through winter. New shoots sprout above the spreading roots and stolons to so plants eventually make an attractive and edible groundcover.

The fruits that follow the flower shows couple just enough sweetness with a rich, unique aroma so they are, if picked dead ripe, delicious plucked right off the plants into your mouth or mixed with, say, your morning cereal. They are pea-sized and somewhat of a show in themselves. The bright red berries hang on the plants for a long time, well into winter, making a perfect Christmas decoration in situ.

Lingonberry is native to colder regions throughout the northern hemisphere. This fruit is the Preiselbeere of the Germans, the kokemomo of the Japanese, the puolukka of the Finns, the wisakimin of the Cree, the airelle rouge of the French, the keepmingyuk of the Inuit—and the lingon of the Swedes. In English, the plant parades under a number of monikers, including partridgeberry (Newfoundland), cowberry (Britain), foxberry (Nova Scotia), mountain cranberry, and rock cranberry.

If you grow lingonberry, give it the same soil conditions as its relatives, blueberries, mountain laurels, and rhododendrons. To whit: Well-drained soil that is high in organic matter, very acidic, and not too fertile.