Springtime, In My Basement

|

| Ramps, now sprouting |

|

| Ramps, now sprouting |

|

| Forget about the nuts; yellowhorn is worth growing even just for its flowers |

|

| Nanking cherry stems are hidden behind the oodles of fruit this plant bears |

Mar 9: Philadelphia Flower Show: FRUIT GROWING SIMPLIFIED

Mar 10: Philadelphia Orchard Project: LECTURE AND HANDS-ON WORKSHOP ON PRUNING FRUIT TREES, SHRUBS, AND VINES

Mar 16, Thetford, VT: FEARLESS PRUNING

April 6, Maine Garden Day (Lewiston, ME): FRUIT GROWING SIMPLIFIED, MULTI-DIMENSIONAL VEGETABLE GARDENING

April 10, Rosendale (NY) Library: BACKYARD COMPOSTING

April 20, Berkshire Botanical Garden (Stockbridge, MA), GROW FRUIT NATURALLY, BLUEBERRIES: RELIABLE & EASY TO GROW, HEALTHFUL, & DELICIOUS

April 28, WV Master Gardener’s Assoc (Flatwoods, WV): MY WEEDLESS GARDEN

May 11, Margaret Roach’s Garden (Copake Falls, NY): BACKYARD FRUIT LECTURE (morning), GRAFTING WORKSHOP (afternoon)

May 16, Brookside Gardens (Wheaton, MD): MY WEEDLESS GARDEN

June 1, The Cloisters (NYC): MEDIEVAL FRUITS YOUCAN GROW TODAY

————————————

The official start for this year’s growing season, which I count as the day when I sow my first vegetable seeds, will begin momentarily. Actually, the season should have already been underway, as of February 1st, but I put in my seed order a little late so am tapping my foot and (im)patiently waiting for the seeds to arrive in the mail. That first sowing is, of course, indoors, and the seeds will be onions, leeks, and celery. The most interesting of the three, as far as growing, is onion.

Down in my cold basement I dug last season’s begonia bulbs (actually, they are tubers, or thickened, underground stems) out of storage. I tucked them in among some wood shavings in an old aquarium last autumn. In contrast to the big, fat amaryllis bulbs, the begonia bulbs didn’t look like much more than rough, brown clods of soil. Moved to warmth, with the sawdust kept moistened with a bit of water — too much and the tubers will rot — those lifeless-looking lumps should sprout leaves, and then, by June, flowers. The appeal of the begonias, which I grew from dust-like seeds a couple of years ago, is that the foliage is attractive and the fire-engine red flowers are, in contrast to those of amaryllis, proportional to the size of the leaves and the plant, and they’re borne nonstop right up until autumn.

Down in my cold basement I dug last season’s begonia bulbs (actually, they are tubers, or thickened, underground stems) out of storage. I tucked them in among some wood shavings in an old aquarium last autumn. In contrast to the big, fat amaryllis bulbs, the begonia bulbs didn’t look like much more than rough, brown clods of soil. Moved to warmth, with the sawdust kept moistened with a bit of water — too much and the tubers will rot — those lifeless-looking lumps should sprout leaves, and then, by June, flowers. The appeal of the begonias, which I grew from dust-like seeds a couple of years ago, is that the foliage is attractive and the fire-engine red flowers are, in contrast to those of amaryllis, proportional to the size of the leaves and the plant, and they’re borne nonstop right up until autumn. |

| Impatiens in Puerto Rico rainforest, El Yunque |

|

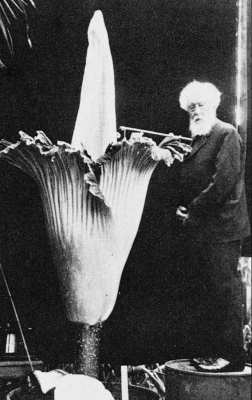

| Hugo de Vries and amorphophallus, 1937 |

|

| Flying Dragon poncirus |

|

| Meiwa kumquat |