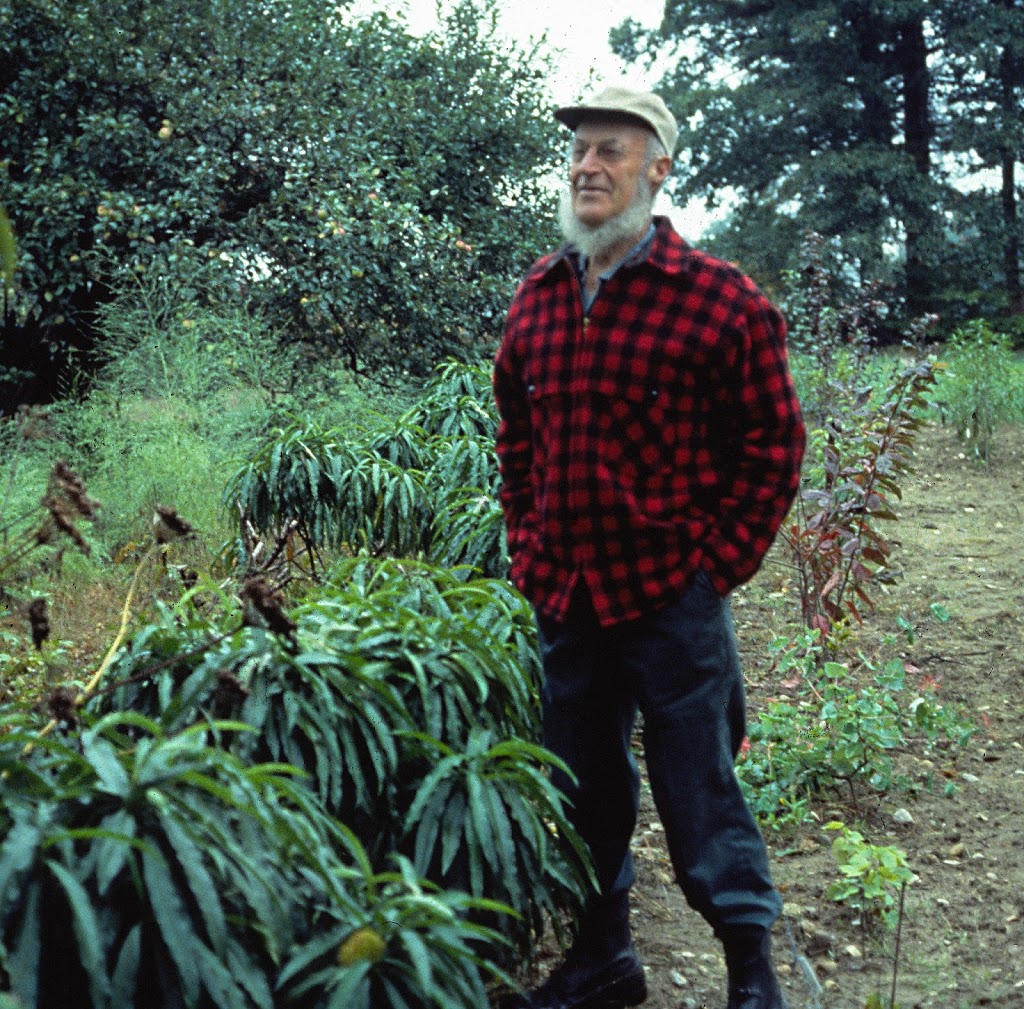

A book giveaway, a copy of my book GROW FRUIT NATURALLY. Check out my new video Life on the Farmden and reply to this post with what other plants, aside from those mentioned or shown, you think I should be growing here on the farmden. I’ll choose a winner randomly from all the replies.

—————————————-

Two plants have been disappointments this year.

Goji berry (Lycium barbarum), the first, has been touted as a wonder food, effective for diabetes, high blood pressure, poor circulation, fever, malaria, cancer, erectile dysfunction, dizziness, and ringing in the ears, and for reducing fever, sweating, irritability, thirst, nosebleeds, cough, and wheezing. It’s also used — this Chinese plant has a long history of use in Chinese medicine — to strengthen muscles and bone, and as a blood, liver, and kidney tonic. Wow!

As amazing as this plant is purported to be, it’s easy to grow. Too easy, in fact, which is one of the problems growing it. Lanky, arching, thorny canes grow from the base of the plant, taking root wherever they touch ground. Turn your back on a planting it soon becomes a tangled mass of thorny canes.

But that must be worth it, considering the miraculous benefits of the berries, right? Like so many miracles, this miracle is pretty much unsubstantiated.

The flavor, then, must make the plant worth growing, right? Wrong. The berries taste awful. Worse, they taste poisonous. And, in fact, like other members of the deadly nightshade family, which does admittedly, include tomato, pepper, potato, and eggplant, goji does contain some toxins that cause adverse reactions in some people.

Still, if you believe in miracles and happen to like the flavor, goji is easy enough to grow and bears the first season, so may be worth growing. Not for me, though.

——————————————

Back in 1975. I wrote a short piece — my first garden writing, in fact — for Organic Gardening magazine about Gardener’s Delight cherry tomato. “It brings back the tangy flavor of [tomatoes of] a century ago,” I wrote (and it’s now a century and a quarter, and then some), “ . . . their tangy, sweet-tart flavor explodes in your mouth.”

Now, here in the 21st century, we have better tomatoes than were available back in 1975, mostly in the form of a lot of excellent heirloom varieties. And because of one relatively new, hybrid cherry tomato, Sungold, that tops all other cherry tomatoes as far as I’m concerned.

This year, after many decades without it, I decided to grow Gardener’s Delight again to see how it compared. The plants grew well and bore quickly. The fruits, however were awful, with mushy texture and bland, mushy flavor. “Blame it on the weather” would be a convenient explanation. In my experience, weather’s effect is not that significant on tomato flavor. My more discriminating taste buds? I don’t think so; the difference between what I remember (and wrote) and what I now taste is too great.

I feel bad, like an old friend has gone to pot.

One more explanation might bring hope. Gardener’s Delight is an open-pollinated variety. Whoever supplied the seed could have accidentally allowed some cross-pollination with another tomato variety. The tomato gets rave reviews from some web reports; other reports concur with me. I’ll try again, with a different seed source.

—————————————-

Every gardening season has it’s quirks, but this year has been the quirkiest yet, a perspective reflecting decades of gardening in four different states.

Oddly enough, the season started off being quirky by being so conventional, or, at least, by being what was supposed to be so conventional. That is, temperatures gradually and steadily warmed in spring, without intervening freezing or torrid spells.

Okay, cicadas were predicted. Still, they were strange and right here, at least, much more abundant than they were last time around, 17 years ago. They’ve left a legacy of browned ends of stems dangling from trees along roadsides. I look forward to not seeing that again for 17 years.

Japanese beetles are surely no strangers around here, making there entrance, as I mentioned a few weeks ago, just as the cicadas were making their exit. But the strange — and very welcome — quirkiness of this year’s beetle invasion is that it pretty much ended soon after it began. Stink bugs, likewise expected by now, have yet to make their entrance.

Perhaps this summer’s Japanese beetle quirk is related to the weather quirk. No, not the nice (for humans) spring temperatures which, being below ground, the beetles hardly would have noticed. Weather quirks included June’s incessant rainfall, more than twice the average, followed by July’s throbbing heat, more than 5°F above the average (which would have been higher had not the last week in July been so comfortable).

Another pest that hardly reared its head here was Mexican bean beetle, which I’ve battled for the past 20 or more years. The reason might be the biological sprays I tried, a mix of Entrust (derived from a bacterium collected from the soil of an abandoned sugar mill in the Virgin isles), Azamax (an extract from the tropical neem tree), along with commercial extracts of hot pepper and garlic. Dense bean foliage and my attempts to limit the sprays only to the bean plants made for less than thorough coverage, leading me to guess that something else might also be a factor. The weather again?

Another quirk: dragonflies. I’ve never seen so many of them as this year.

The final quirk concerns breadseed poppy, a self-seeding annual flower that has showed up reliably every year at various locations of its own choosing around my gardens and beyond. This year: almost none. My guess is that the reason has something to do with something I did. But what? Who knows?

The above observations are very casual and very local, mostly right here on my farmden along the Wallkill River in the Hudson Valley. I wonder: Cicadas notwithstanding, has anyone else experienced garden strangeness this year?

————————————–