ONE OF THE GREATEST APPLES

/5 Comments/in Fruit/by Lee ReichOl’ TJ was Spot On

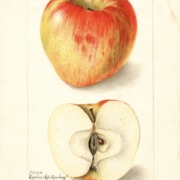

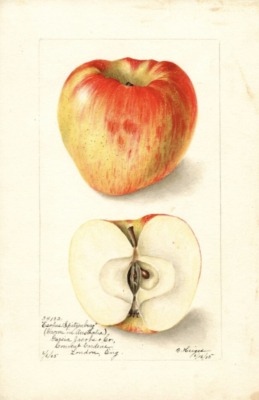

Thomas Jefferson was right: Spitz is one of the greatest. Apples, that is. Esopus Spitzenberg, to use the variety’s full name, was the variety that T.J. preferred over all others from his Monticello orchard. And soon it will be coming into perfection here. Or, I should say “would be coming into perfection here.”

Watercolor from my book “Fruit: From the USDA Pomological Watercolor Collection“

That was years ago, when I grew Spitz.

This time of year, back then, the fruits would not be still hanging from the branches. Read more

NO NEED FOR A MELANCHOLY EXIT

/2 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichThe Valuable Dead Stuff

Dead leaves on the ground, dead stems on trees and shrubs, dead plants where flowers and vegetables once strutted their stuff — how forlorn the yard can look this time of year. The urge is to tidy things up by blowing or raking leaves out of sight, pruning away unwanted branches, and ripping dead plants out of the ground.

Cover crops and brussels sprouts

Garden cleanup has its virtues, but can do more harm than good if taken to excess. For instance, many gardeners like to clear Read more

THREE BEAUTIFUL QUINCES

/10 Comments/in Flowers, Fruit/by Lee ReichTwo Hardly Edible Quinces

A lot people wonder about eating those orbs hanging from quince bushes. After all, everyone has heard of eating quinces, even if few people — these days, at least — have actually tried them.

In most cases, the answer to the question about whether you can eat the fruit depends on how hungry you are. The reason is because most of the “quinces” that you see are what are called “flowering quinces” (Chaenomeles spp.), grown mostly as ornamentals.  Read more

Read more