SOIL MATTERS

/3 Comments/in Gardening, Soil, Vegetables/by Lee ReichPlastic on My Bed?!

You’d be surprised if you looked out on my vegetable garden today. Black plastic covers three beds. Black plastic which, for years, I’ve railed against for depriving a soil of oxygen, for its ugliness, for — in contrast to organic mulches — its doing nothing to increase soil humus, and for its clogging landfills. Actually, that insidious blackness covering my beds is black vinyl. But that’s beside the point. Its purpose, like the black plastic against which I’ve railed, is to kill weeds. Not that my garden has many weeds. But this time of year, in some beds, a few more sprout than I’d like to see.

Actually, that insidious blackness covering my beds is black vinyl. But that’s beside the point. Its purpose, like the black plastic against which I’ve railed, is to kill weeds. Not that my garden has many weeds. But this time of year, in some beds, a few more sprout than I’d like to see.

The extra warmth beneath that black vinyl will help those weeds get growing. Except that there’s no light coming through the vinyl, so most weeds will expend their energy reserves and die. And this should not take long, depending on the weather only a couple of weeks or so.

So, first of all, I’m covering the ground for a very limited amount of time.

Furthermore, that the black vinyl is not manufactured specifically for agriculture. It’s recycled billboard signs, available on line from www.billboardtarps.com and other sources. For larger scale use, farmers use the material sold for covering silage.

Old billboard signs or silage covers also improve on black plastic mulch because they are tough. Each time they’ve done their job they can be folded up for storage for future use to be used over and over.

Heavenly Soil

Decades ago, I made a dramatic career shift, veering away from chemistry and diving into agriculture. In addition to commencing graduate studies in soil science and horticulture, I rounded out my education by actually gardening, reading a lot about gardening, and visiting knowledgable gardeners and farmers, including well-known gardener (and better known political and social scientist) of the day, Scott Nearing.

I had just dug my first garden which had a clay soil that turned rock hard as it dried, so I was especially awed, inspired, and admittedly jealous of the soft, crumbly ground in Scott’s garden. What a surprise when someone who had worked with Scott for a long period told me how tough and lean his soil had been when he started the garden. A number of giant compost piles were testimonial to what it takes to improve a soil.

I had just dug my first garden which had a clay soil that turned rock hard as it dried, so I was especially awed, inspired, and admittedly jealous of the soft, crumbly ground in Scott’s garden. What a surprise when someone who had worked with Scott for a long period told me how tough and lean his soil had been when he started the garden. A number of giant compost piles were testimonial to what it takes to improve a soil.

I thought of Scott and his soil as I was planting peas a few days ago. My chocolate-colored soil was so pleasantly soft and moist that I could have made a furrow with just by running my hand along the ground. For a long time I’ve appreciated the fact that the soil in my vegetable garden is as welcoming to seeds and transplants as was Scott’s.

And my dozen or so compost piles, inspired by Scott’s, are testimonial to those efforts.  The soil in my permanent vegetable beds is never turned over with a rototiller or garden fork; instead, every year a layer of compost an inch or so deep is lathered atop each bed, and no one ever sets foot in a bed. That inch of compost snuffs out small weeds, protects the soil surface from washing away, and provides food myriad beneficial microbes (and, in turn, for the vegetable plants).

The soil in my permanent vegetable beds is never turned over with a rototiller or garden fork; instead, every year a layer of compost an inch or so deep is lathered atop each bed, and no one ever sets foot in a bed. That inch of compost snuffs out small weeds, protects the soil surface from washing away, and provides food myriad beneficial microbes (and, in turn, for the vegetable plants).

All sorts of what I consider gimmicky practices attract gardeners and farmers each year: aerated compost teas, biochar, nutrient density farming, fertilization with rock dust, etc. Yet one of the surest ways to improve any soil is with copious amount of organic materials such as, besides compost, animal manures, wood chips, leaves, and other living or were once-living substances. A pitchfork is a very important tool in my garden.

Uh Oh, A Soil Problem

Not all is copacetic here on the farmden.

I make my own potting soil for growing seedlings and larger potted plants. It’s a traditional mix in that it used some real soil. Just about all commercial mixes lack real soil because it’s hard to maintain a sufficient supply that is consistent in its characteristics.

Early this spring, as usual, I sifted together my mix of equal parts compost, peat moss, perlite, and garden soil. This year, NOT as usual, germination of seeds and seedling growth has been very poor. Just today, I re-sowed all my tomato seeds in a freshly made mix from which I excluded soil.

I’m not 100 percent sure that the soil in the mix is the culprit, but it is suspect. I have a small pile of miscellaneous soil that I keep for potting mixes and other uses.  Recent additions to that pile were an old soil pile from a local horse farm and soil from a hole I was digging to create a small duck pond. The latter was poorly aerated subsoil.

Recent additions to that pile were an old soil pile from a local horse farm and soil from a hole I was digging to create a small duck pond. The latter was poorly aerated subsoil.

Seedlings are growing well in my new mix composed only of compost, peat moss, and perlite.

A Podcast and a Workshop

/3 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee ReichI was recently on Joe Lamp’l’s gardening podcast talking about “uncommon fruit.” They’re worth growing because they’re easy, they’re ornaments, and, with few or no pest problems, they’re easy. And they have excellent and unique flavors. Listen to the podcast here.

Also, I’m hosting a pruning workshop at my New Paltz, NY farmden:

The Season Begins

/6 Comments/in Design, Vegetables/by Lee ReichOne More Thing? Ha!

I have one more important task to do before planting any vegetables this spring, and that is the annual mapping out of the garden, something I generally put off as long as possible.

In theory, mapping out my garden should be easy. I “rotate” what I plant in each bed so that no vegetable, or any of its relatives, grows in a given bed more frequently than every 3 years.  In practice, I mostly pay attention to rotation of plants most susceptible to diseases, which are cabbage and its kin (all in the Brassicaceae), cucumber and its kin (Cucurbitaceae), tomato and its kin (Solanaceae), beans and peas (Fabaceae), and corn (sweet or pop, in the Gramineae).

In practice, I mostly pay attention to rotation of plants most susceptible to diseases, which are cabbage and its kin (all in the Brassicaceae), cucumber and its kin (Cucurbitaceae), tomato and its kin (Solanaceae), beans and peas (Fabaceae), and corn (sweet or pop, in the Gramineae).

Crop rotation prevents buildup of disease pests that overwinter in the ground; removing host plants eventually starves them out. (Insect pest are more mobile, so crop rotation has less impact except in very large plantings.) So one year a bed might be home to cucumbers, melons or squashes. The next year that bed might host cabbage, broccoli, kale, Brussels sprouts, or cauliflower. Then tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, or eggplants. And finally, the fourth year, back to cucumbers. Simple enough.

It would also be nice to rotate carrots and other root vegetables with leafy vegetables, such as lettuce, and fruiting vegetables, such as tomatoes.  Root, leafy, and fruiting vegetables have somewhat different nutrient needs, so in the ideal garden these crops are rotated to make best use of soil nutrients.

Root, leafy, and fruiting vegetables have somewhat different nutrient needs, so in the ideal garden these crops are rotated to make best use of soil nutrients.

And I do like to get the most out of my garden and confuse potential insect pests by grouping different kinds of plants within a bed.

Are you beginning to understand why I put off committing my garden plan to paper each spring?

Pea Problem(s)

Peas present one more wrinkle in my vegetable garden planning. A few years ago they stopped bearing well, collapsing with yellowing foliage not long after they bore their first pods.

A few years ago they stopped bearing well, collapsing with yellowing foliage not long after they bore their first pods.

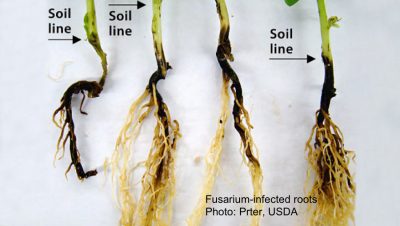

Further investigation has narrowed the problem to – probably – one of two diseases: fusarium or aphanomyces. Both, unfortunately, are long-lived in the soil so that a 3 year rotation does nothing to keep them in check.

Fortunately, I have two vegetable gardens. So, for the past few years I have banned peas from my north garden, planting them only in my south garden, in which they do get rotated. After a few more years, I’ll move the pea show to my north garden and leave my south garden pea-less. I’ve also been planting the varieties Green Arrow and Little Marvel, both of which are resistant to fusarium, at least.

Unfortunately, the problem is more likely aphanomyces, for which resistant varieties do not exist. Aphanomyces is a water mold, so thrives under wet conditions. So my tack will also be to keep any peas planted in my vegetable garden on the dry side, not even turning on the drip irrigation in those beds.

I’ll also be checking the plants more closely for symptoms. Plants infected by fusarium have a red discoloration to their roots.  Plants infected by aphanomyces have fewer branch roots and what roots there are lack the plump, white appearance of healthy roots.

Plants infected by aphanomyces have fewer branch roots and what roots there are lack the plump, white appearance of healthy roots.

Pea Solution?

I’m also testing out root drenches with compost tea for my peas.

Yes, yes, I know I have dissed compost tea in the past. Mostly, its benefits, if any, have been overstated. But compost microbes have more chance of surviving in the dark, moist, nutrient-rich environment of the soil than on a leaf, where the stuff is often sprayed. I’m drenching the soil with the tea, not just giving the surface a spray, as usually recommended, so a lot more bacteria, fungi and friends are finding their way down there.

I see no reason (and research does not support) of going to the trouble of making the usual compost tea, which is aerated and might be fortified with such things as molasses.  My tea is nothing more than the liquid strained from compost soaked in water, then applied with a watering can at the base of the pea plants.

My tea is nothing more than the liquid strained from compost soaked in water, then applied with a watering can at the base of the pea plants.

I’ve done this for a couple of seasons but have nothing definite to report yet. The hard part is sacrificing a bed as a control. Perhaps this year.