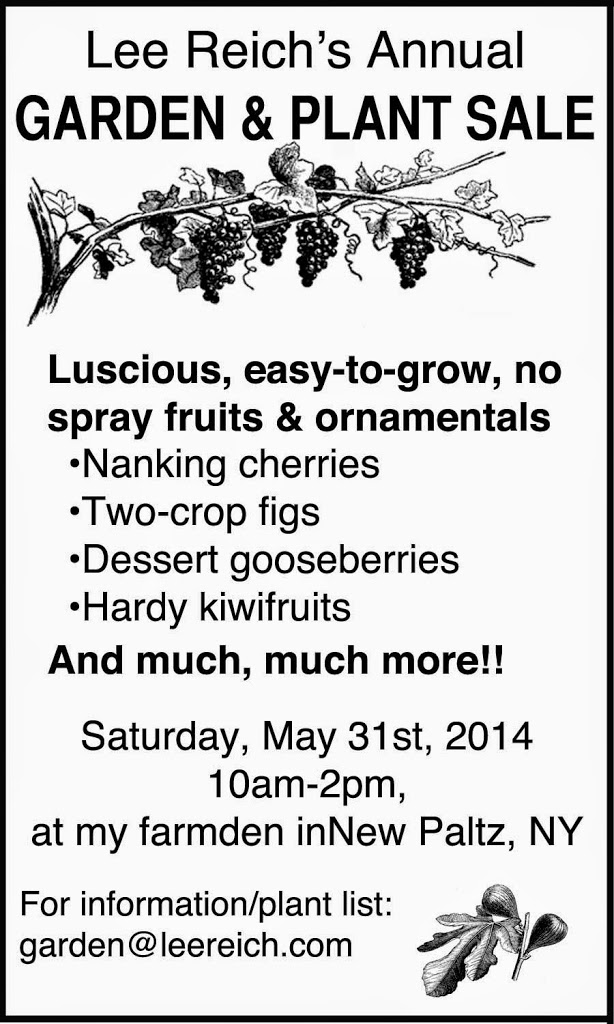

Lee Reich’s Annual Garden & Plant Sale

/0 Comments/in Gardening/by Lee A. Reich

Luscious, easy to grow, no spray fruits and ornamentals.

- Nanking Cherries

- Two-crop figs

- Dessert gooseberries

- Hardy kiwifruit

And much more!

Saturday, May 31st 2014

10am – 2pm

at my farmden in New Paltz, NY

Contact Lee for more information.

CICADAS THREW A MONKEY WRENCH INTO MY PRUNING

/5 Comments/in Pruning/by Lee A. ReichUPCOMING EVENTS SCHEDULE

April 26th, 2014: “Pruning Nuts”, New York Nut Growers Association spring meeting at the Cornell University Cooperative Extension of Suffolk County, 423 Griffing Avenue, Riverhead, NY, on Saturday, April 26, 2014 from 9:30 until 3:00, http://www.nynga.org.

April 27th, 2014: 2-5:30, “Pruning workshop” with Lee Reich, at my farmden in New Paltz, NY. Contact me for more information. This hands-on (my hands) workshop will cover: The best time to prune; the “tools of the trade”; Plant response to various kinds of pruning cuts; pruning demonstrations. Contact me for registration and more information.

May 3rd, 2014: 2-5:30, Make your own trees at the “Grafting workshop, at my New Paltz, NY farmden. The how, why, and when of grafting; demonstration of 2 easy kinds of grafts; and then make your own pear tree to take home. Contact me for registration and more information.

April 27th, 2014: 2-5:30, “Pruning workshop” with Lee Reich, at my farmden in New Paltz, NY. Contact me for more information. This hands-on (my hands) workshop will cover: The best time to prune; the “tools of the trade”; Plant response to various kinds of pruning cuts; pruning demonstrations. Contact me for registration and more information.

May 3rd, 2014: 2-5:30, Make your own trees at the “Grafting workshop, at my New Paltz, NY farmden. The how, why, and when of grafting; demonstration of 2 easy kinds of grafts; and then make your own pear tree to take home. Contact me for registration and more information.

May 10th, 2014: “Weed-less Gardening”, in conjunction with Garden Conservancy Open Day at Margaaret Roach’s garden in Copake Falls, NY, 11 am, http://awaytogarden.com/my-2014-events/may-10-open-garden-plant-sale-plus-weed-less-gardening-talk-lee-reich/

—————————————–

And now, on to the post . . .

Are the 6,000 acres of forest preserve behind my farmden mocking me? Almost every day, weather permitting, I grab pruning shears, a lopper, and a pruning saw, and head outdoors to snip, lop, or saw at least some stems or limbs from my trees, shrubs, and vines. Up there in the forest, no one is doing any pruning yet everything seems copacetic.

Let the forest laugh. My efforts here aren’t for naught. If a large limb crashes down from a forest tree, the forest as a whole is none the worse for wear. If a limb cracks off the honeylocust that is supposed to shade my deck . . . well, that’s not good for the deck, for the health of the tree, or for the desired shade. Similarly, a forest doesn’t feel the loss of one tree to pests or diseases. Not so for the stately crabapple gracing a front lawn.

So I prune to help keep my trees healthy. A tree with good form is stronger, less likely to lose a limb. And if a limb does surrender to the weight of snow, a crisp pruning cut of the frayed stub leads to quick healing of the wound. I prune off any tarry, black growths on my plum trees so that they can’t further the spread of black knot disease. I prune my kiwi and grape vines so that each remaining stem can bathe in the sunlight and air that is inimical to the spread of fungal diseases.

As gardeners, farmdeners, and farmers, we demand more from our plants in terms of flowers, fruit, and/or form that a forest does from its individual trees. Pruning, in removing some potential buds, directs a plant’s energy into fewer buds, making for more spectacular blossoms and more luscious fruits.

I prune also because it’s fun. Gardening is more than just good food, pretty plants, and a chance to “work” outside with the sun warming my back. It’s also, for me at least, about watching plants respond to my ministrations, rewarding me if the response is positive, and providing a learning experience if the response is negative.

———————————————-

Last year’s invasion of cicadas has thrown a monkey wrench into my usual pruning. Cicadas didn’t feed on stems, but use them as a nursery in which to lay eggs. Ms. Cicada prefers 1/3-1/2” inch thick stems which is, unfortunately, the thickness of many stems on my fruit trees, most of which show at least some damage. The slits weaken the stems so they are more likely to break off and have less energy for new growth so can support less fruit, physically and physiologically.

Last year’s invasion of cicadas has thrown a monkey wrench into my usual pruning. Cicadas didn’t feed on stems, but use them as a nursery in which to lay eggs. Ms. Cicada prefers 1/3-1/2” inch thick stems which is, unfortunately, the thickness of many stems on my fruit trees, most of which show at least some damage. The slits weaken the stems so they are more likely to break off and have less energy for new growth so can support less fruit, physically and physiologically.

Mostly, I’m going to wait to prune these plants to see what they have planned in terms of flowers. If they flower heavily, which is doubtful, I’ll shorten stems enough so that they don’t break under their weight of fruit. I’ll also reduce the number of fruits to the number I estimate the weakened plants can support.

I’ll go ahead more or less with my normal pruning on stems or trees that don’t flower. Probably a little less severely than usual so that the plants can put all their energy into growing as much as possible to build up their energy reserves.

In either case, good soil enriched with plenty of compost, mulching, and timely watering will provide good growing conditions to put injured plants on the road to recovery.

————————————————

What of the future? Those slitted stems no longer house eggs. The eggs hatched last summer a month and a half after being laid, and then, the nymphs dropped to the ground. After burrowing in the soil, the next 16 years will be spent growing and feeding on roots.

Roots! My poor trees. Perhaps I should have cut off all the slitted stems last year and burned them before the eggs hatched. But that would have severely debilitated the plants. Oh well, nothing’s to be done except give the plants good growing conditions and hope for the best. As always, Mother Nature has the upper hand.

————————————————

A lot of gardeners sow their tomato seeds too early and the result is spindly plants. The time to sow the seeds is about 6 weeks before the average date of the last killing frost, which, around here, is April 1st. No joke.