BIOCHAR

Enthusiasm

A couple of years ago a gardening friend shared with me her excitement about a biochar workshop she had attended. “I can’t wait to get back into my garden and start making and using biochar,” she said.

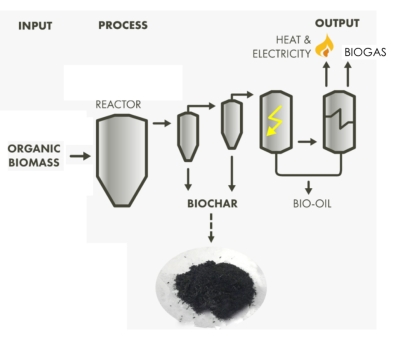

Biochar, one of gardening’s relatively new wunderkinds, is what remains after you heat wood — or other plant material such as rice husks, yard trimmings, or manure — with insufficient air. It’s akin to charcoal, although its physical characteristics vary with the kind of plant material, the amount of air during the burning, and the duration and intensity of the heat.  Rather than releasing the carbon in wood or other material into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide by burning it or allowing it to decompose, the carbon in biochar remains locked up. Less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere means less global warming.

Rather than releasing the carbon in wood or other material into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide by burning it or allowing it to decompose, the carbon in biochar remains locked up. Less carbon dioxide in the atmosphere means less global warming.

And yes, biochar can be made at home — outdoors, because the process gives off varying amounts of methane, hydrogen, and carbon monoxide (commercially captured for use as a fuel). Also a liquid “biofuel.”

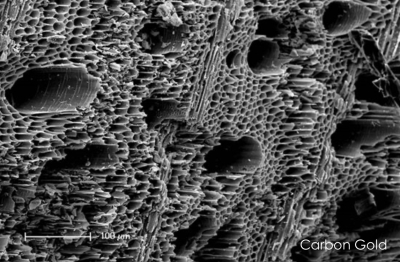

There’s more to biochar. Stirred into the soil, biochar’s myriad nooks and crannies provide an expansive adsorptive surface for microbes and chemicals, natural and otherwise.  It can improve a soil’s ability to retain water and nutrients, and raise the soil pH. It’s many interstices provide home to myriad soil microorganisms. Often the overall effect on plant growth is positive although sometimes it’s negative or without any effect.

It can improve a soil’s ability to retain water and nutrients, and raise the soil pH. It’s many interstices provide home to myriad soil microorganisms. Often the overall effect on plant growth is positive although sometimes it’s negative or without any effect.

Which is Better?

Compost, aromatic and seething with life

Let’s say you have two pounds of wood chips or sawdust. You could make that into biochar, or you could compost it or add it directly to the soil as mulch or mixed in. Added to soil or compost, the wood material decomposes into humus as it feeds microbes which, in turn, feed plants. Humus is soil organic matter, a witch’s brew of compounds that nurtures beneficial soil microorganisms to fend off plant diseases and releases nutrients as it eats away at dead plants and a soil’s rock matrix. That’s not all: It also aggregates clay soils to make air spaces for roots to breathe and sponges up water to keep sandy soils moist.

So, is cooking up a batch of biochar and digging it into the ground really worth the effort? Biochar and raw wood or other plant material have similar benefits although the latter materials have the benefit of feeding soil life, not just providing them with a home, as with biochar.

Biochar is resistant to microbial attack; the carbon that made it less apt to end up in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. The carbon in wood is in a constant state of flux, morphing into soil organic matter and thence carbon dioxide — a good thing; it’s life.

Biochar, if made on a large scale, would require extensive acreage to grow biochar feedstuffs; the attendant disruption of biodiversity and ecosystems, both of which help stabilize climate and provide food for humans. Agricultural and other waste products could be used for biochar production, but diverting these products from from direct soil application would result, worldwide, in a decrease in soil humus and fertility.

Ancient Wisdom?

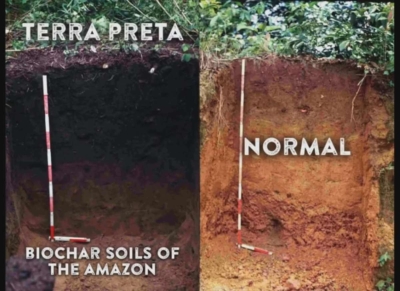

Biochar made headlines a number of years ago as a remnant of agriculture from more than one thousand years ago in the relatively infertile, tropical soils of South America. Although it was hypothesized that creating those dark soils, terra preta, (“black soils”) was deliberate, they probably were an unintended consequence of “slash and burn” agriculture, a primitive but effective way of maintaining fertility. Lush areas of land were periodically burned, and the resultant ash contained minerals to feed crops — for a time.

When the land was exhausted, the planters moved on to another area of lush land, while wild flora and fauna eventually regenerated the spent plot. Slash and burn works as a permanent form of agriculture as long as there’s sufficient land to give each slashed and burned area time to naturally recoup its fertility before being slashed, burned, and cultivated again.

Dark soils are generally a sign of fertile soils. The excitement over terra preta conflates soil that is dark from humus with soil that is dark from biochar. The darkness of humus comes from carbon that is in organic compounds (any chemical compound that contains carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds). Carbon in biochar mostly isn’t bonded to anything; it’s “elementary” carbon. So soil organic matter and biochar are both dark, but much of their effects in soil are quite different.

Good Uses for Biochar

I’m not totally discounting biochar; I see two benefits. The first is for remediation of toxins, be they arsenic, cadmium, or other heavy metals, or pesticides, that have made their way into a soil. Toxins can be adsorbed and held within biochar’s tiny pores.

A second benefit of biochar is for trees in urban landscapes. In such settings, growth of tree roots is restricted and the soil within the restricted spaces becomes compacted over time. Enter biochar.  Mixed into planting holes for these citified trees, nutrients will be retained and the biochar will improve drainage in the same way that perlite or vermiculite does in your houseplant’s potting mix.

Mixed into planting holes for these citified trees, nutrients will be retained and the biochar will improve drainage in the same way that perlite or vermiculite does in your houseplant’s potting mix.

By not decomposing, biochar’s benefits will be long lasting for that leafy, urban dweller.

We use a wood burning stove. The fine ash and chunks of charred wood left over are placed in a garbage can. Can we use this on our garden plot and around our fruit trees?

The fine ash is high in potassium and alkaline — all good for plants but not if used to excess. I would sprinkle it on the ground, dispersing it over a wide area. The charred wood is essentially charcoal, biochar-ish. Won’t hurt anything but als probably won’t help.

Biochar interests me greatly. As you note though, its effects can be highly variable. One year I trialled tomato seedlings in various %ages of biochar/potting mix; the results defied explanation. 100% biochar gave a predictably poor result, while both the 80% and 30% biochar pots grew much better than the 50% biochar pot and the 0% biochar pot. All pots received the same water and liquid fertiliser.

I have successfully used crushed homemade biochar to increase the moisture- and nutrient-holding capacity of the very sandy soil under my lawn. The area is now able to sustain a reasonably healthy lawn where previously it was sparse.

The possibilities for urban biochar usage are very promising – your readers may wish to google Stockholm’s use of biochar in their urban plantings.

Thanks Lee for the blog post. As a silviculturist on public lands in the SW – I think there is a huge potential for biochar – especially when confronting the wildfire crisis. That is, there exists an enormous amount of woody biomass above ground. With that there are two outcomes in my mind for all this above ground biomass (carbon) – it can burn up in wildfire or we can help put it back into soil! A place like the Hudson Valley of NY may not be the best application of biochar however, the alkaline soils of New Mexico or other aridisol soil could be a marvelous place to apply biochar. Thanks again!

I would imagine that under the aerobic conditions of a wildfire, most of the wood goes up in smoke. As far as the partially burned biochar that remains, is there anything more to do with it other than just leave it in place?

The issue is more what to do with all of this biomass before the fire happens. Traditional saw timber markets do not exist for low value small diameter material (fuel). Biochar presents an opportunity to harvest the ‘fuel’ and convert it into something that could be applied to aridisols and other alkaline soils. There’s a research group at USDA looking at applications to remove the material before it burns aerobically in a wildfire – burn it through pyrolysis – and apply it to soils that would benefit from this treatment.

Or grind it as mulch.