OLD ENEMIES RETURN

Damn Damping Off

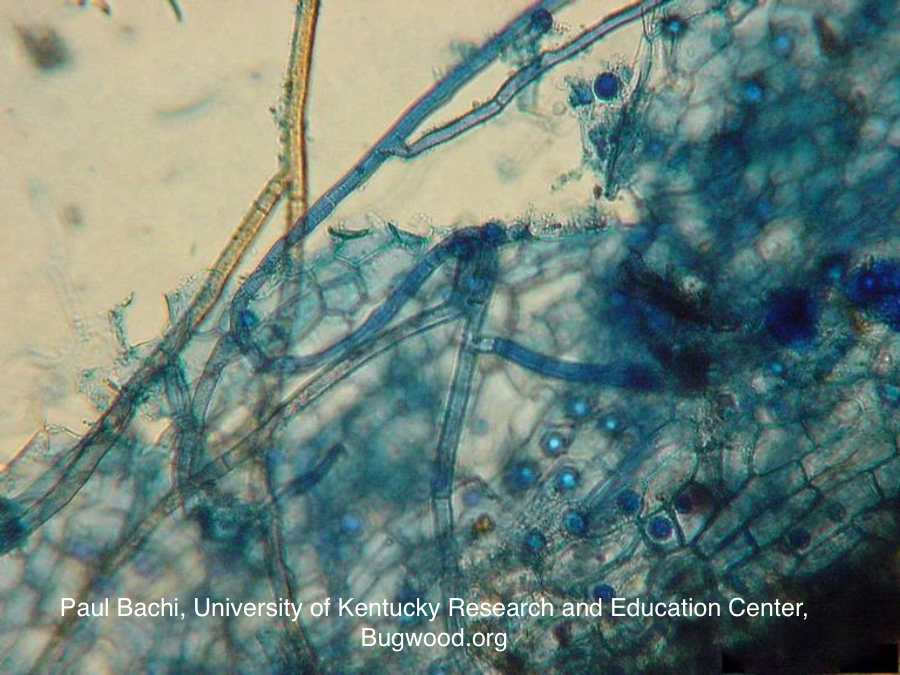

My first garden foe, which I haven’t seen for years, recently sneaked into the greenhouse. Damping-off sounds pretty bad but not as bad as its scientific names, probably Rhizoctonia or Pythium, which, along with a few other fungi, can cause damping off.

My introduction to damping-off disease came before my first plants even made it out to my first adult garden. At the time, I was living in a relatively dark apartment, a converted motel room, and was eager to start seedlings. I sowed all sorts of seeds in peat pots, stood them in a little water, then crowded them together on all the shelf space that could be mustered.

Young sprouts never appeared in some of the pots. In others, seedling emerged, then toppled over, their “ankles” reduced to a withered string of rotted cells, unable to support the small plants physically or physiologically.

Conditions created were perfect for any one of the damping-off culprits: overly wet soil, cool temperatures, low light, weak growth, stagnant air. How was I, a beginning gardener, to know? I soon learned to avoid the disease by, in addition to providing good light, providing sufficient fertility to promote strong growth that resists disease, paying careful attention to watering, and using a fan to keep air moving.

My seeds now go into a potting mix containing sufficient perlite to help drain away excess water. Sterile potting mixes, such a those sold bagged, are presumably free of damping-off culprits. But sterile mixes also lack beneficial soil microorganisms so afford free rein to any culprits that make their way into a mix. My home made potting mix isn’t sterilized.

A couple of other tricks also limit damping-off disease. Spreading a thin layer of dry material, such as perlite, vermiculite, sand, or kitty litter (calcined montmorillonite clay) on the surface of the potting mix keeps the stem area dry. And there is some evidence that chamomile tea (cooled) controls damping-disease if sprayed on plants and soil surface.

I’m considering this most recent damping-off incident to be a fluke, so far affecting just a single cabbage plant in a whole flat of cabbages.

Second Garden, Second Foe

That first garden, my first garden, was short-lived. Not because of any horticultural trauma, but because it was begun on August 1st and, before the following year’s gardening season got underway, I had moved. My new site, home to my second adult garden, was also home to my second garden foe, which has been lurking in the wings of every garden ever since then.

Quackgrass with runner

That foe is and was quackgrass, also known as witchgrass, couchgrass, and, botanically, Elytrigia repens. It is small consolation that quackgrass isn’t only my problem; this native of Europe, north Africa, and parts of Asia and the Arctic, is now a worldwide weed.

Soon after turning over the soil to begin that second garden, quackgrass invaded. With vengeance. Long story short: I had read of the benefits of mulches in smothering weeds; in Wisconsin, where I lived, lakes were becoming clogged with water weeds, which municipalities harvested; I convinced a water weed crew to dump a truckload of water weeds on my front lawn; my quackgrass expired beneath a slurpy mulch of quackgrass laid atop the ground pitchfork by pitchfork.

Foe #2, Defeated (Sort Of)

Quackgrass has always stalked the edges of my gardens, waiting for a chance to slink in. It spreads mostly by underground rhizomes, which are modified stems that creep just beneath the surface of the ground. Growing tips of quackgrass rhizomes are pointed and sharp enough to penetrate a potato. Given time, quackgrass develops an underground lacework of rhizomes.

My current garden never had a quackgrass problem, mostly because I never tilled it or turned over the soil. Tilling or hand-digging it, as I did in my second garden, compounds quackgrass problems because each piece of rhizome can grow into a whole new plant.

My current hotspot of quackgrass found a fortuitous opening, creeping in among a planting of coral bells beneath a very thorny rose bush along the edge of my vegetable garden. Quackgrass rhizomes must be removed or the quackgrass smothered, either difficult to do among the coral bells and the rose.

My plan is to sacrifice the coral bells and pull out every rhizome I can find. In soft soil this time of year, long pieces can be lifted with minimum breakage or soil disturbance. A mulch with a few layers of newspaper, topped with a wood chip mulch (part of weed management, as described in my book Weedless Gardening) will suffocate any overlooked rhizome pieces trying to sprout. In the absence of other plants among which the rhizomes could sprout, mulching alone can do in quackgrass, as it did in my second garden.

My plan is to sacrifice the coral bells and pull out every rhizome I can find. In soft soil this time of year, long pieces can be lifted with minimum breakage or soil disturbance. A mulch with a few layers of newspaper, topped with a wood chip mulch (part of weed management, as described in my book Weedless Gardening) will suffocate any overlooked rhizome pieces trying to sprout. In the absence of other plants among which the rhizomes could sprout, mulching alone can do in quackgrass, as it did in my second garden.

Longer term, barriers around garden edges could prevent quackgrass rhizome entry. Barriers need to be deep or wide. A concrete strip, 6 inches wide and decoratively inlaid with handmade tiles, has been effective elsewhere along my garden edge.

For now, I have to stop writing and get to work on the quackgrass. I have too, after all, because a wrote a book called Weedless Gardening!

This is probably my favorite post you’ve written so far. It’s nice to see reflections back to beginning years as I am still novice.

I wanted to pick your brain on something I heard on a guest interview this week on You Bet Your Garden.

I wasn’t a big fan of Paul Wheaton’s interview but he said one thing that stuck with me:

He recommends growing apples from a seed to get the tap-root. Transplants do not have a taproot.

I thought that was interesting. Have you commented on this before? I am traveling for an interview but will flip through two of your books to see if you commented on this anywhere previously.

Thank you!

I already know the part about size, and bearing fruit later, etc. I just wanted to focus the brain picking on the tap-root component.

There’s no great advantage to an apple having a tap root. Most of its feeder roots, like those of other plants, are in the surface areas of soil. There are many downsides to growing apples from seed: trees will be large, making them harder to spray, prune, thin, and harvest; large apple trees are less efficient than smaller trees so yield less per unit area. On the other, seedling apple trees are tough trees. I assume Paul Wheaton suggested grafting the seedling apple tree. If not grafted, it’s unlikely to bear a good-tasting fruit — 1 in 10,000 chance of it tasting good, according to apple breeders.

is quack grass worse than wire grass?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wiregrass_Region

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wiregrass_Region

Wire Grass is the worse when it gets in to your compost pile or leaf pile.

whoops, first link was supposed to be https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elymus_repens

Do you have a recipe for your potting mix here or in one of your books? (I don’t recall seeing it in your books.) Thank you in advance.

It should be in my books. Anyway, here it is: equal parts sifted compost, garden soil, peat moss, and perlite, plus a cup of soybean meal per 10 gal mix. Sometimes I throw in some powdered kelp also.