THANK YOU EPHRAIM

Foxy Grapes

Early each fall I come upon a most delicious fragrance, reminiscent of jasmine, at a certain point as I walk along the rail trail near my home. No flower claims responsibility for that aroma. Wild grapes, dangling in ripe clusters from low hanging vines, are the source. That scent begs a taste, whose quality you quickly discover pales by comparison with that of the perfume. Wild grapes are downright sour.

Now go to your grocer’s shelf and take a deep whiff of the grapes there. Hardly a hint of aroma — unless the grapes happen to be the variety Concord, a commercial grape variety that captures the essence of our wild grapes. And Concord’s berries are indeed edible, being much larger and sweeter that their wild counterparts.

Concord isn’t the only grape variety that captures that unique aroma — the “foxiness,” as it is called — of our wild grapes. It’s just that Concord is the most common one.

As for that descriptor of flavor, foxiness, various interpretations have been offered over the years. Perhaps foxes eat these grapes. Perhaps the name refers to the resemblance of the leaves to the tracks left by foxes. Perhaps the aroma suggests that of fox. American botanist and nurseryman William Bartram (mentioned in last week’s post) wrote, “The strong, rancid smell of [wild grapes’] ripe fruit, very like the effluvia arising from the body of the fox, gave rise to the specific name of this vine.” Nonetheless, Concord grapes have wide appeal.

A Grape for the Millions

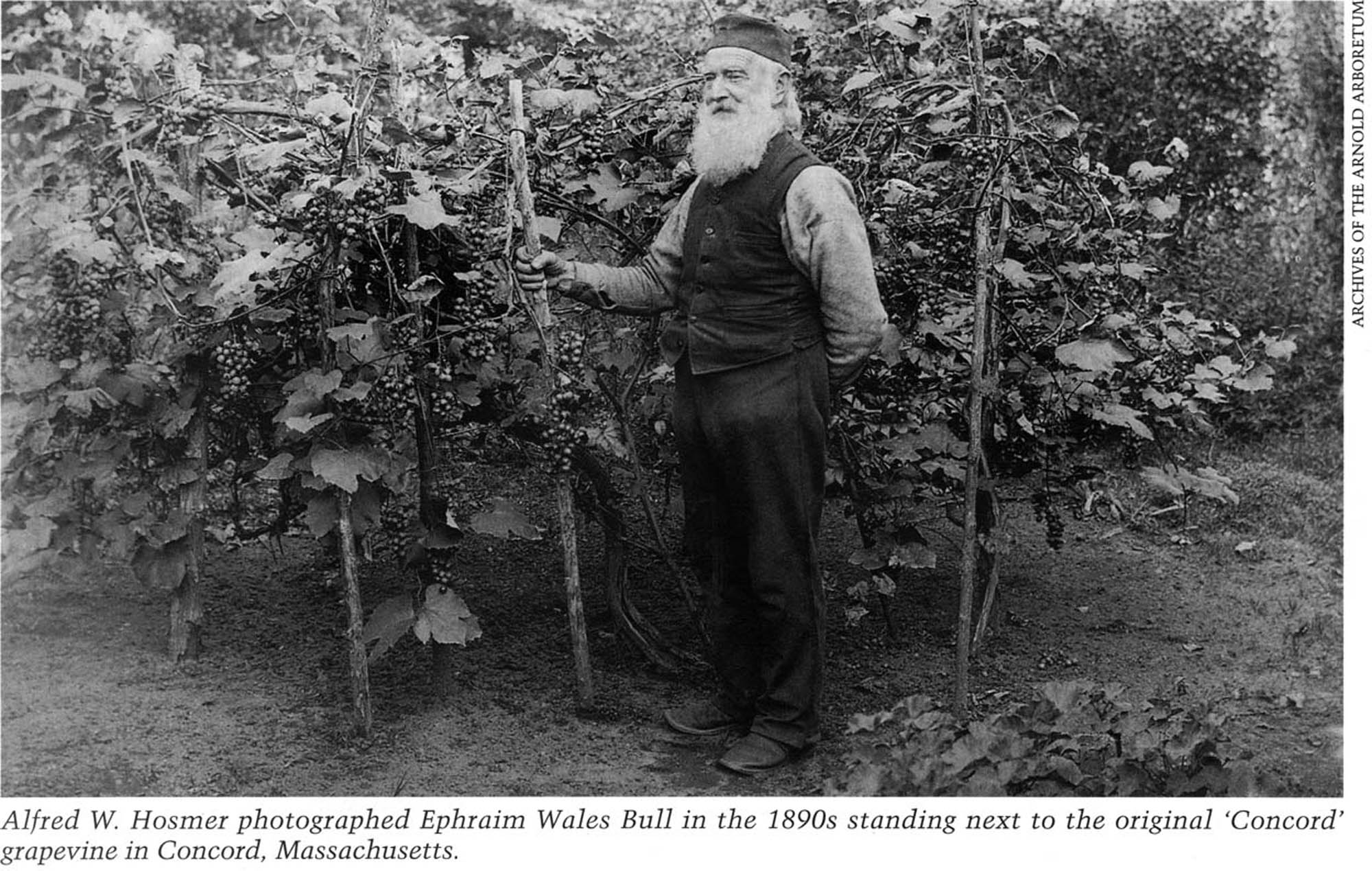

The man we have to thank for Concord is Ephraim Bull, a retiring soul who resided in Concord, Massachusetts from his birth in 1805 until his death in 1895. He planted the seed that was to become Concord in 1843; the vine bore its first fruits in 1849. That fruit was exhibited before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in 1852, was introduced by a nursery in 1854, and the rest is, as they say, history.  By 1865, Concord was awarded a prize by the American Institute as the best grape for general cultivation. Horace Greeley, the donor of the prize, declared Concord “the grape for the millions.”

By 1865, Concord was awarded a prize by the American Institute as the best grape for general cultivation. Horace Greeley, the donor of the prize, declared Concord “the grape for the millions.”

And planted by the millions it was. Among Concord’s qualities is its adaptability to varying soils and climates. You’ll find Concord vines growing in almost every state, even California, where European grapes thrive. For that matter, you’ll even find Concord planted in Europe itself, as a backyard variety. And while we may pooh-pooh those sweet wines made from Concord, they are popular in Italy even though, or perhaps because, it is illegal there to sell Fragolino, as wines made from American type grapes are called.

International Exchanges

With a tough skin that slips off to release a layer of sweetness huddled just beneath, its jellied flesh, and its foxy flavor, Concord is the archetypal American grape. Contrast Concord with Thompson Seedless, its mild flavor, sweetness, and crunchy flesh are characteristic of European, or vinifera, grapes.

Vineyard of European wine grape

European grapes (Vitis vinifera) are a different species from American grapes (Vitis labrusca), and the differences in fruit are quite dramatic. European grapes, such as the aforementioned Thompson Seedless, are richer in sugar, also making them them keep better and possible to dry to become raisins. Their flavor is delicate, as are their skins and seeds. They make what are considered the best wines. Hence their usually being called European wine grapes.

Early colonists brought European wine grapes to the New World. These grapes were unable to tolerate eastern states’ severe winter cold and native pests to which American grapes were accustomed. Plantings were eventually established, mostly in the milder western regions of our country. Relatively recently, though, with careful selection of site and some innovative techniques, some growers have succeeded in growing European wine grapes in the East.

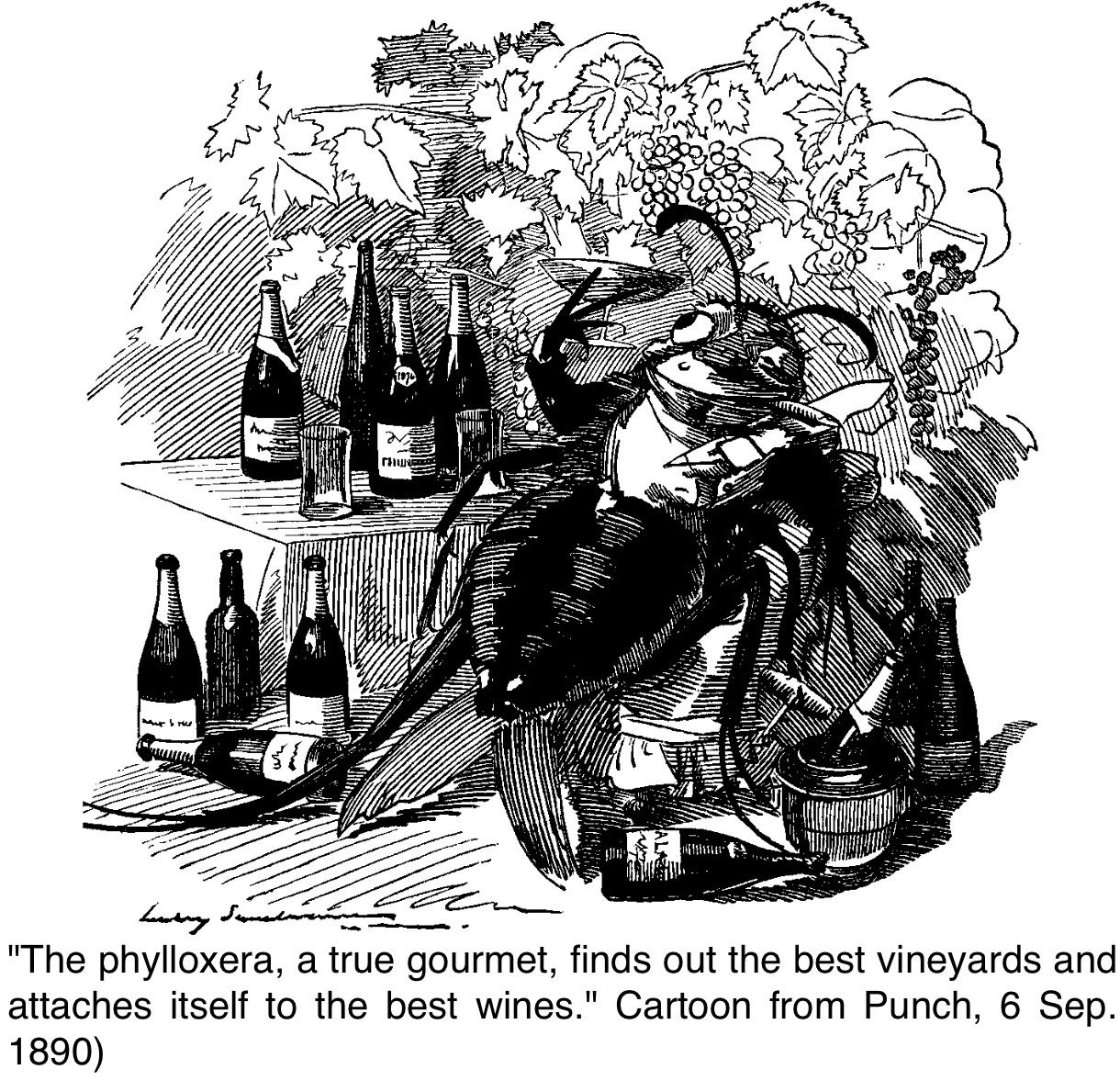

That transport of grape genetics became a two-way street, and American species found their way into Europe. Hitchhiking with those vines was a native pest, phylloxera, an aphid relative to which the European vines were very susceptible. Their effect there was devastating. Most of Europe’s wine grapes were wiped out just after the middle of the 18th century.

That devastation spurred hybridization of European wine grapes with their American counterparts. The resulting hybrids have some pest resistance and cold tolerance. They also vary in fruit characteristics, depending on their parents lying somewhere on the spectrum between V. vinifera and V. labrusca. Other American grape species also often went into the genetic stew.

Hybridization was carried out on this side of the Atlantic as well as in Europe. While Concord might be the poster child of American grapes, it is actually a hybrid determined through genetic testing to be one-third European wine grape. That’s not surprising since Ephraim Bull noted that the seedling that became Concord was a wild plant growing near a field of Catawba vines. Catawba was known to be a hybrid.

Brianna grape, my favorite, a hybrid more on the foxy end of flavor spectrum

Concord had many characteristics that soon made it one of the most popular grapes in eastern North America. The plants are vigorous and usually productive, and relatively resistance to insect and disease pests. Add to that list of qualities Concord’s relatively late blossoms, rarely nipped by late spring frosts, as well as the fruit’s ability to hang well and the rich, deep color the berries develop. Within a year of its introduction it was being grown halfway across the country.

It’s true that some people just don’t like that foxy flavor. A friend reflexively spits out any grape with such strong flavor. I happen to prefer the bold flavor of foxy grapes to the delicate, overly sweet flavor, to me, flavor of European wine grapes. What are your pleasures?

Edelweiss grape, another of my favorite foxy hybrids

Thanks for reminding me to go out and collect some wild grapes as they make an excellent jelly. I usually add a few trusses of local Concord’s just to bulk it up.

I also have been meaning to write and thank you for your posts as they are always informative. So many garden writers now only print transcripts of their podcasts and I really appreciate your thoughtful articles.

Thank you. It’s always nice to get feedback after sending my writing out into the void of the internet.

I enjoy your posts. This one reminded me of how much I miss Concord grapes. We raised enough in SE Michigan for our families enjoyment — but here, in central MN, they are seldom available locally. I’ve also enjoyed tasting wild grapes while trail riding on my horse since I could reach the higher bunches of grapes that hadn’t been picked by trail walkers.

I love these grapes. Nobody sells them that I can find. Perhaps I’ll have to grow them myself. Do you recommend a source?

Around here, you can find Concord fruit available seasonably in supermarkets and farmers’ markets. Most nurseries, mail order and stores, sell Concord plants in spring.