THE TRUTH ABOUT RAIN

Plenty of Water Here. Really?

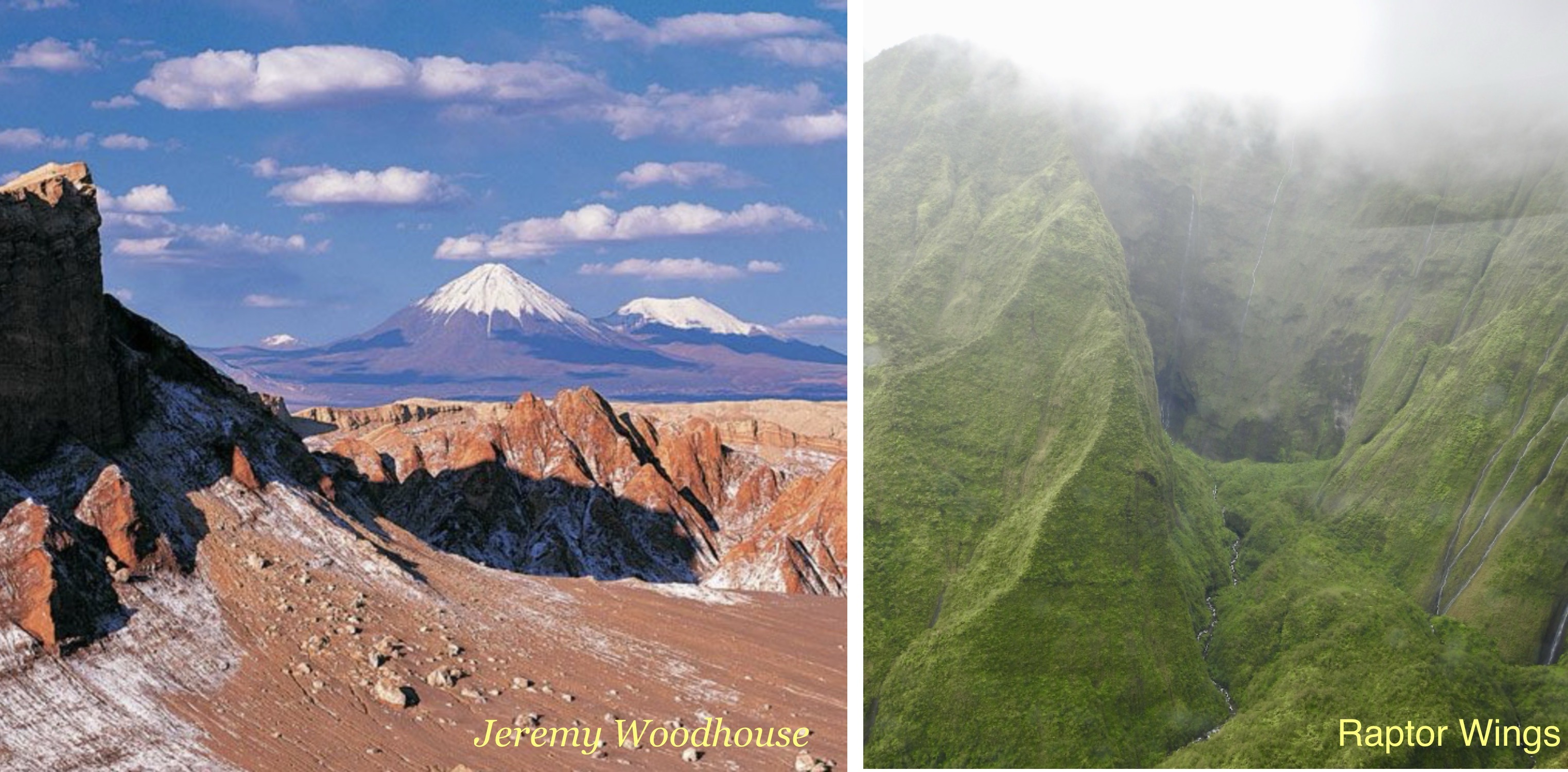

During an entire year, a meager three-hundredths of an inch of rain falls on Arica, Chile, yet halfway across the Pacific in the Hawaiian Archipelago, Mount Waialeale receives a sopping 460 inches. The climate on my farmden, and throughout northeastern U.S., is more or less congenial for growing plants — at least those plants we enjoy in our gardens.

We average about four inches of rainfall each month throughout the year, and this amount complements nicely the inch depth of water per week recommended for most garden plants. Four inches of rainfall each month is more than enough water to supply the 33 gallons used by a tomato plant, the 54 gallons needed by a corn plant, even the 1800 gallons quaffed by a single large apple tree!

Average annual rainfall shrinks to half our 45 inches as you move towards the western part of our country, and less than half that amount if you go even further west. Travel north near the Pacific coast and you’re back in a climate averaging about 45 inches of annual rainfall.

Water, Inviting and Holding

So much for theory. Problem is, wherever you are, rain is not always in the right place at the right time. Four inches of rain dumped from the sky on the Fourth of July, with none again until the first of August, would meet July’s quota here. But much of that water might run off the surface of the soil or down through the soil beyond the reach of roots.

One way to remedy a feast or famine situation is to coax all water falling from the sky into the soil.

Soil moisture meter

Small catch basins built up around individual trees and shrubs keep rainfall in place for these plants. Organic mulches like straw or leaves help water penetrate the soil by preventing raindrops from pounding, then sealing, the surface.

Illustration adapted from my book THE EVER CURIOUS GARDENER

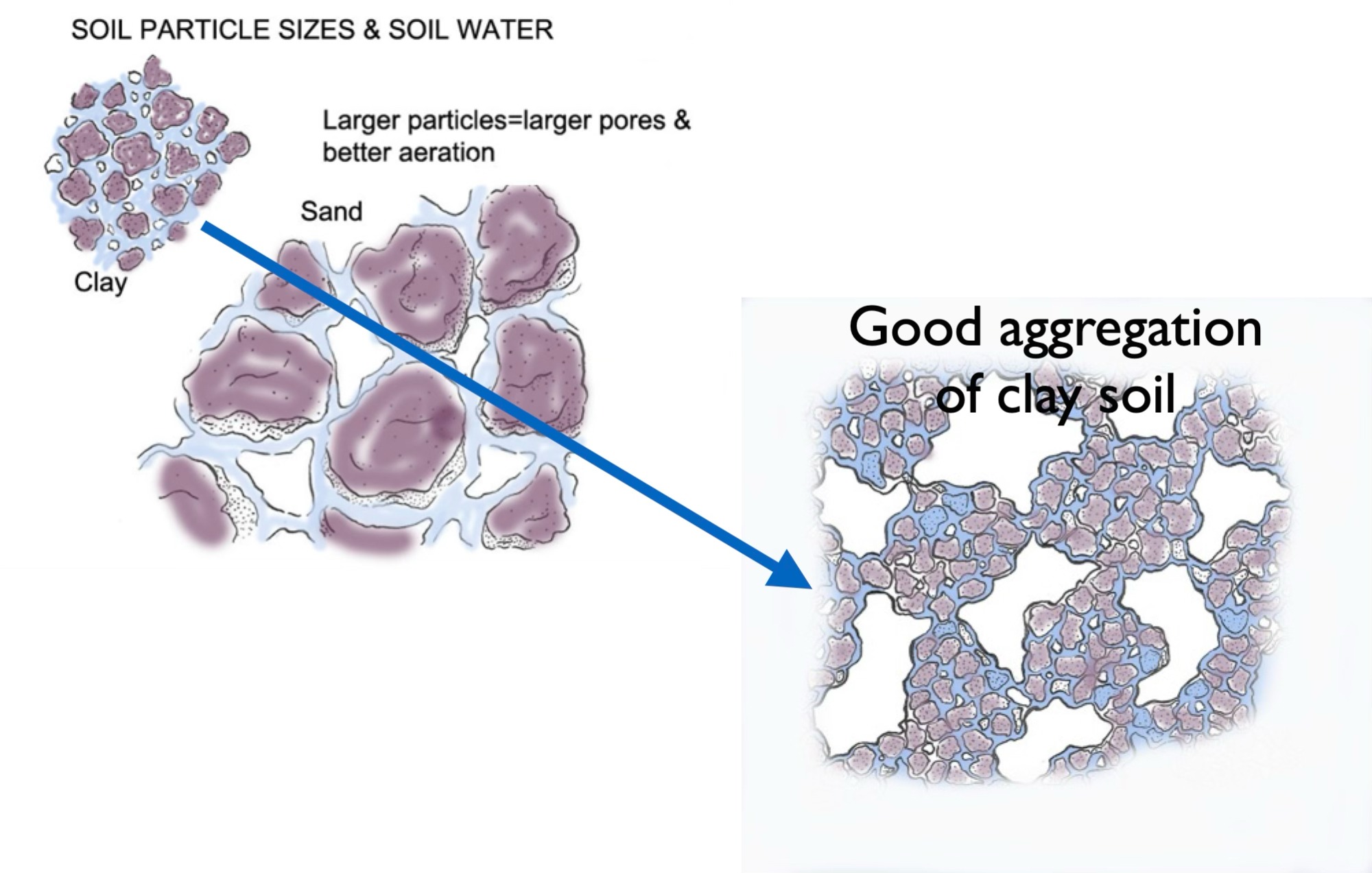

Infiltration is generally not a problem in sandy soils, because of the large spaces between the large sand particles readily admit water. But water can puddle on the surface rather than seep into the tiny spaces between clay particles — unless those soils have been treated well so that they have good structure, i.e. aggregation of the tiny clay particles to create larger particles with commensurately large spaces between them, just like sandy soils.

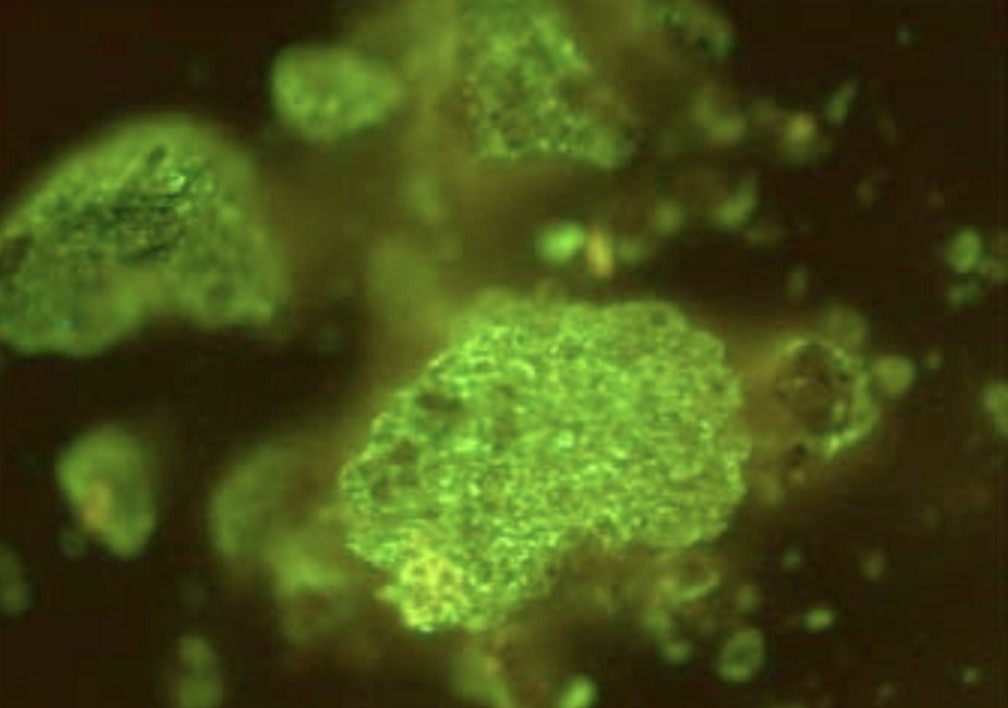

Good soil structure is achieved by minimizing tillage and doing it only when the soil is just moist, neither too wet nor too dry. Or, even better, no tillage, which, along with cover crops and regular additions of organic materials such as compost, straw, or leaves, builds up soil humus which bind soil particles together into stable aggregates. The “glue” for these aggregates has been identified as glomalin, a protein produced by certain fungi.

Glomalin

Once water is in the ground, those organic materials also hold it there. They do this by preventing evaporation from the soil surface and, mixed with the soil, acting like a water-holding sponge.

Once water is in the soil and held there, why waste it on weeds? A full-grown ragweed plant sucks about 2 gallons of water per day from the soil, water that could be put to better use plumping up juicy, red tomatoes. Timely weeding keeps water in the soil for the plants we choose to cultivate.

Options for Watering

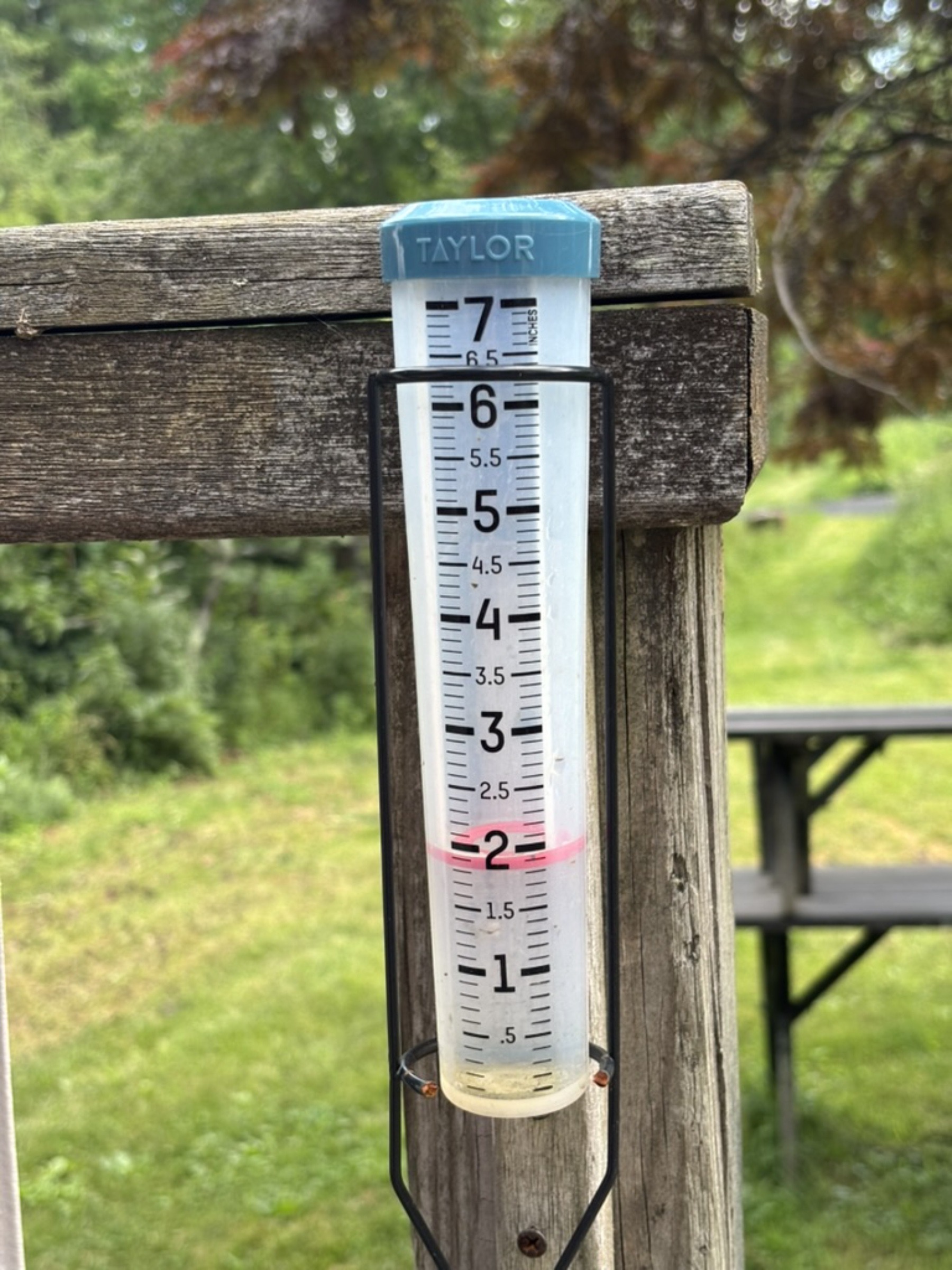

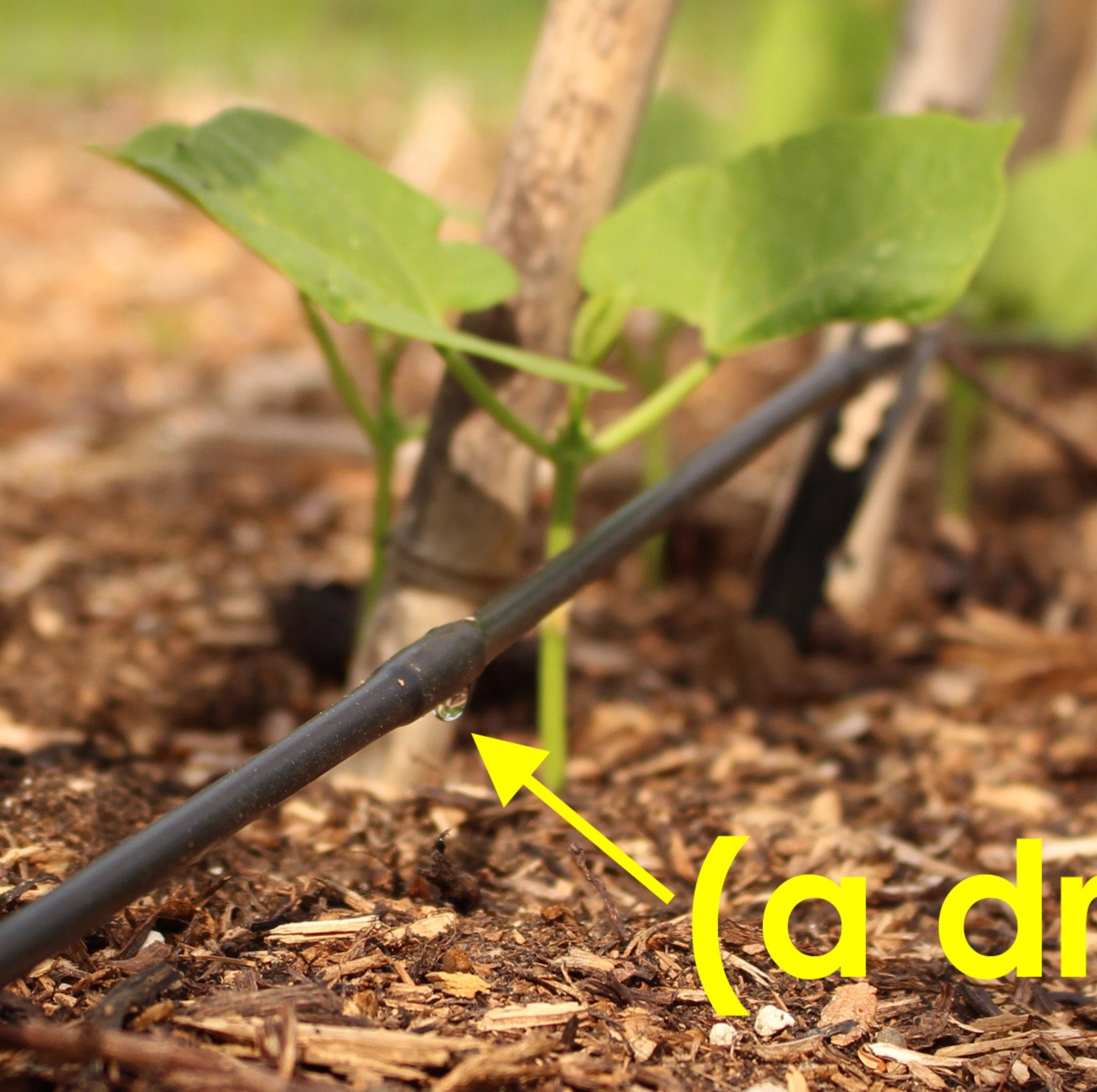

Okay, for all your water conservation efforts, sometimes you just gotta water your plants. There are two approaches here: Water either deeply and infrequently with a sprinkler, watering can, or bucket. Or water lightly and frequently with a drip irrigation system.  Either way, the amount of water to use translates to the same as our average rainfall, one inch (about a half-gallon per square foot) applied once each week, or 1/7th of an inch applied every day or throughout the day.

Either way, the amount of water to use translates to the same as our average rainfall, one inch (about a half-gallon per square foot) applied once each week, or 1/7th of an inch applied every day or throughout the day.

Note that that one inch weekly is an approximation. The actual amount of water needed varies somewhat with the weather and the plant. More water exits leaves and the soil surface with hot, windy, and/or sunny weather. Larger plants suck up more water from the ground; same goes for growth stage — when plants are fruiting, for example. And plants vary in their rooting depth, with deeper rooting plants able to top into more water reserves in the ground.

Triage

When your time or energy is running short — often the case when hand watering and using sprinklers — you might want to first quench the thirst of those plants that need water the most. The first plants to suffer from thirst are annual flowers and leafy vegetables like lettuce, spinach, and cabbage, as well as any perennials or trees you set out just this spring.  Moderately drought resistance vegetables include bean, carrot, cucumbers, eggplant, pea, pepper, and summer squash. If time or water is scarce, hold off on watering parsnip, winter squash, sweet potato, tomato, and watermelon whose deep roots tide them over under dry conditions.

Moderately drought resistance vegetables include bean, carrot, cucumbers, eggplant, pea, pepper, and summer squash. If time or water is scarce, hold off on watering parsnip, winter squash, sweet potato, tomato, and watermelon whose deep roots tide them over under dry conditions.

Roots of full-grown trees and shrubs run deep into the soil, so these plants — especially if they are native, and thus well adapted — can wait longest for water.

Lawn tolerates drought by going semi-dormant and tawny, then perks up when moist conditions return. So here on the farmden, at least, it’s low priority for any water. Actually, it’s no priority.

I’m using drip emitters to give my tomatoes and peppers a gallon (based on their ratings) of water every other day. I really should collect the output of a couple of them to verify the amount, but they are all looking real good and I just had my shoulder replaced so if I hold off a bit, they should be okay.

If they are pressure compensating drip irrigation emitters, they are engineered orifices which ensure that the water drips out at the stated rate. No need to check it.

Thanks Lee. Really appreciate your column!