NATURE’S DESSERT

What Do I Hear?

Every morning I can hear especially one group of plants crying out to be pruned. It’s the fruit trees. They demand annual and careful pruning. I’m almost finished pruning them, but not quite.

Taste the sweetness of a perfectly ripe pear: that sweetness represents energy, the result of pruning so all limbs bask in energy-generating sunshine. Pruning also helps these trees strike a balance between shoot growth and fruit production. Pruning removes some potential fruits so that more of the plant’s energy can be funneled into the fewer fruits that remain, fewer but larger and more flavorful fruits.

I started off regular pruning of each of these trees right after they were planted. The first years are important to a fruit tree’s future performance. These are the years to help a tree lay down a permanent framework of branches that can support loads of fruit and not shade each other.

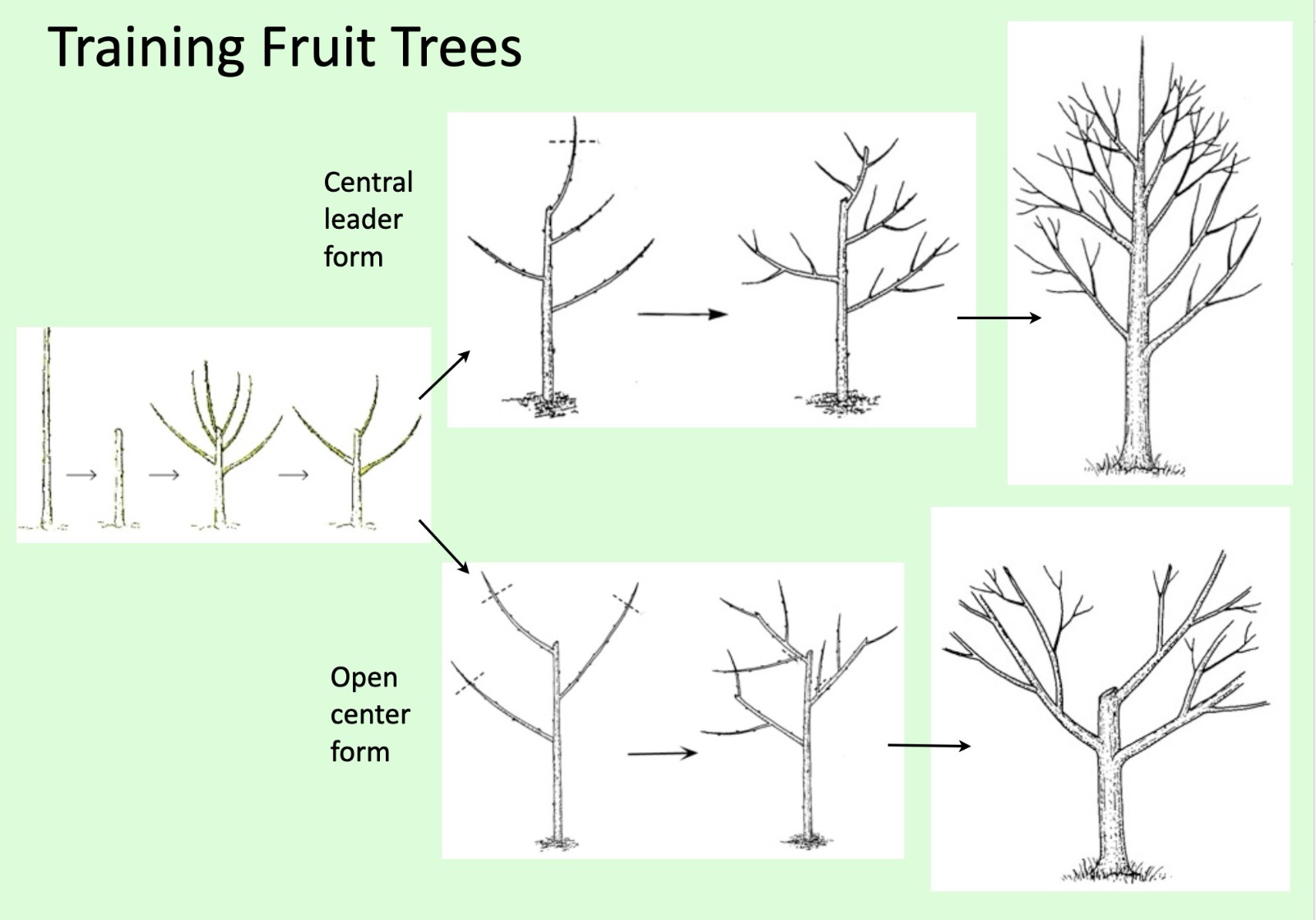

Centuries of fruit growing have spawned many different tree forms, but two predominate: the central-leader and the open-center. The central-leader tree is shaped much like a Christmas tree: a single “leader” flanked by shorter and shorter side branches from the bottom to the top of the tree.

The open-center tree is vase shaped, with three or four main limbs growing outward and upward.

The ideal form for a particular tree depends not only on your whims, but also the plant’s natural growth habit. A peach tree or an Asian plum tree, for instance, cries out to become an open-center shape. At the other extreme are European pear trees, whose natural inclination is to grow upright with a central leader form.

Not that any tree has to follow its natural inclinations. I have convinced some of my trees, through judicious pruning and perhaps branch bending, to take on a different character. Espalier, for instance.

For Starters

I begin pruning any new tree by cutting back broken stems and dead or diseased wood to healthy tissue. If a new tree is only a single stem (known, in the trade, as a “whip”), I shorten it by 1/3 to promote branching.

Typically, the top two or three buds expand to vigorous, upright, new shoots while buds lower down give rise to less vigorous, less upright new shoots. It the tree is destined to a central-leader form, by nature or my training, I cut off all but one of the vigorous, upright shoots before they grow too big, saving one as a continuation of the central leader. Some of the shoots from those lower buds are saved as future side branches. The following year, I follow the same procedure on the extension of the central leader.

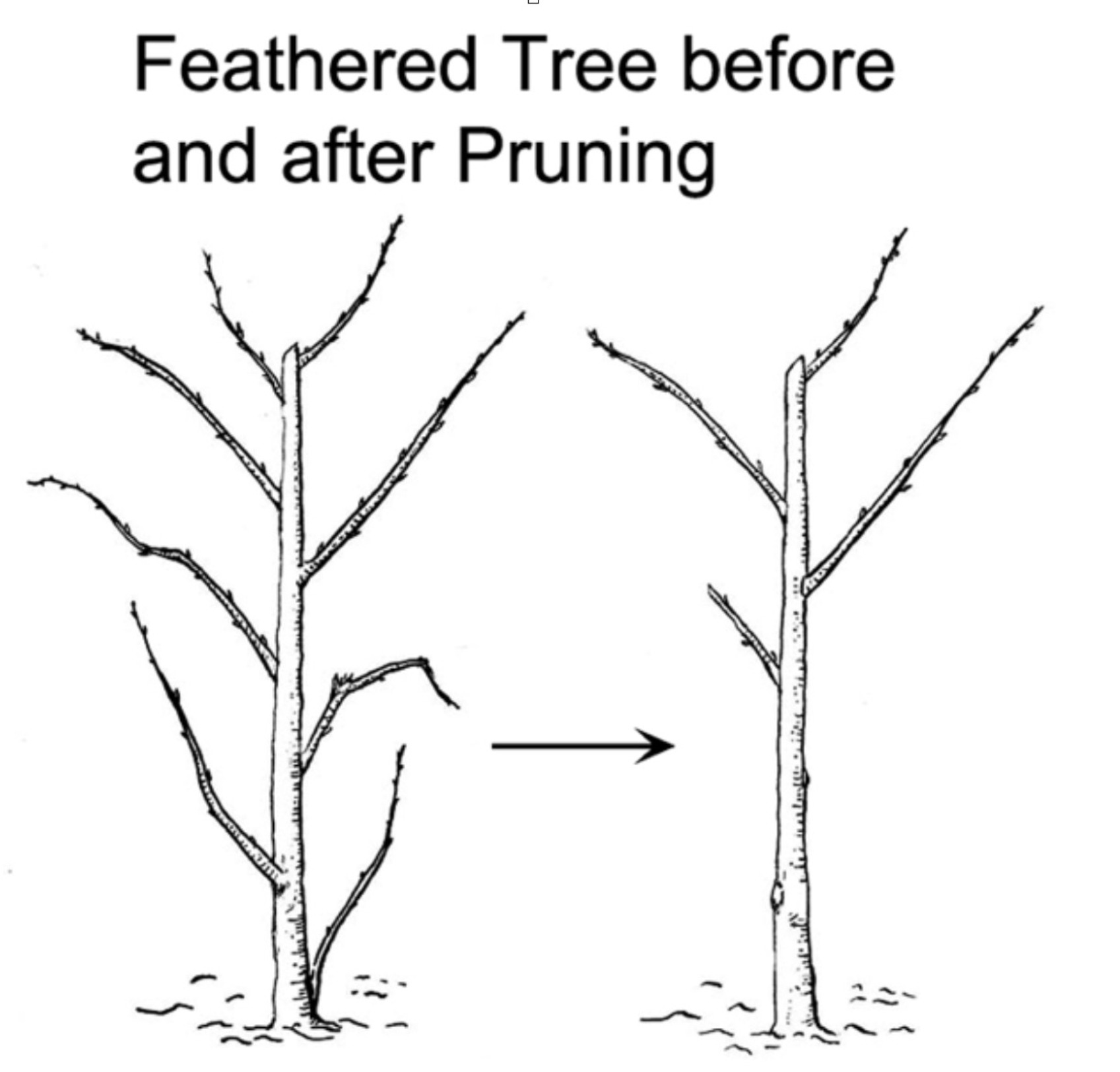

If it is already branched (this one known as a “feathered tree”), I save some well-placed stems and completely cut away all others.

What to save? The ideal branching arrangement for a fruit tree starts two feet from the ground and continues in a spiral arrangement up the trunk with about eight inches between branches. In the case of the open-center tree, I lop off the central stem just above the third or fourth side branch.

Young, central-leader cherry tree

Whether central-leader or open-center, the best side branches are not too, too vigorous. That is, less than about half the thickness of the leader and growing at a wide angle from it. If one side branch decides to show its strength with a narrow angle and upright growth, it gets either lopped off or bent downward. It’s important for the central leader to remain top dog. I’ve used notched pieces of wood, toothpicks, weights or string anchored to the ground to widen a branches spread.  Bending it down makes for a strong attachment to the leader and, as an added attraction, promotes earlier fruiting.

Bending it down makes for a strong attachment to the leader and, as an added attraction, promotes earlier fruiting.

Achieving Balance

As any fruit tree grows, the skill in pruning it is to strike a congenial balance between shoot growth and fruit production. A young tree needs to put lots of energy into growth, to fill its allotted space. Asian pears tend to be overly precocious; I grit my teeth and pull off most or all the fruit from a young tree.

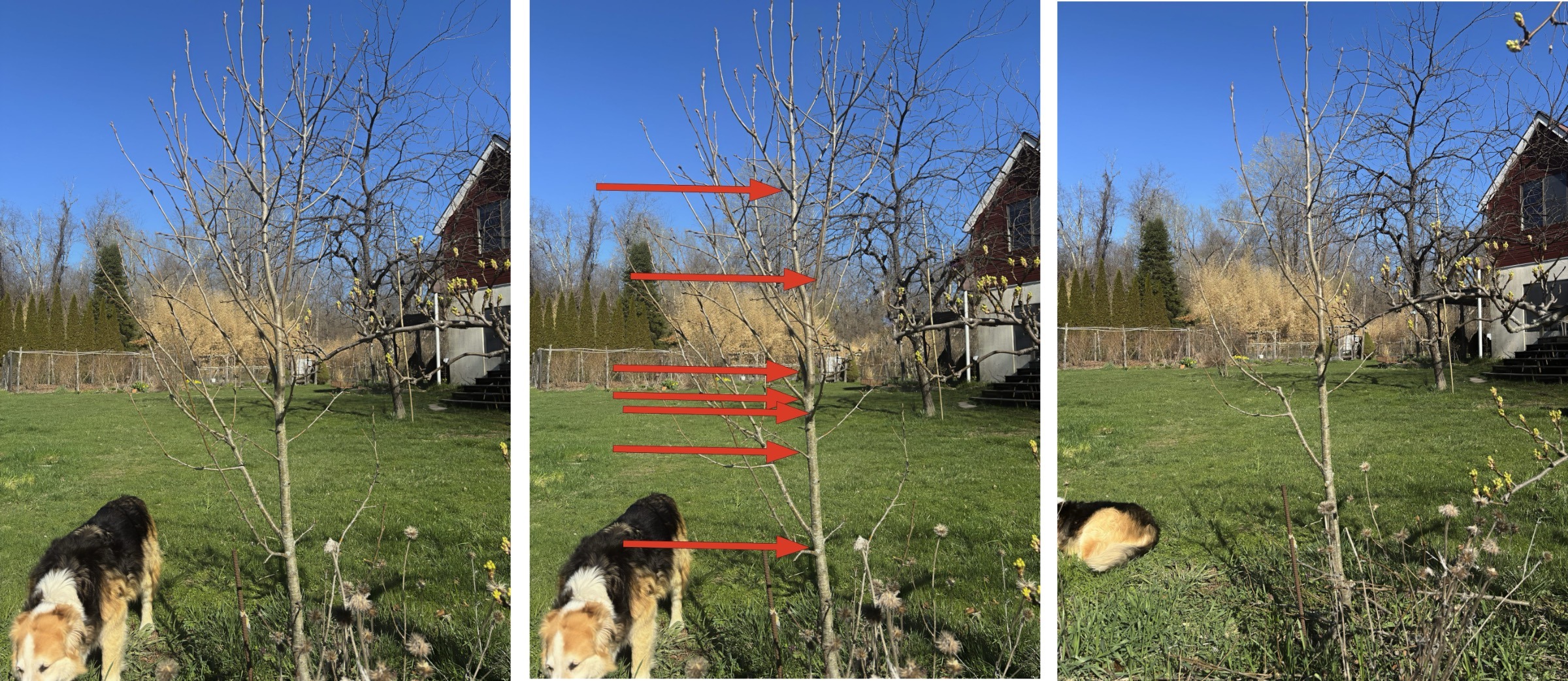

Young pear tree, showing where I prune

For a mature tree, the balance tips towards encouraging more fruit production and less shoot growth. How much to prune to achieve this balance depends on how — or, really, where — a particular tree bears its flowers and how big its fruits are. Especially with large fruits, such as apple and peach, individual fruits tend to be undersized and less sweet if the tree is carrying too much fruit.

A bearing fruit tree is pruned each year by shortening some stems and removing others completely. I shorten stems where I want increased branching. Stems I don’t want — such as vigorous, vertical unfruitful shoots called watersprouts — get cut all the way down or else snapped off when young.

Pruning, of course, can also keep a fruit tree from growing higher or wider than you want. Better than pruning, in this case, is to plant a variety or kind of tree that naturally suits your needs.

One-year-old flower and fruit bearing stems of peach

The kind of tree that you are pruning dictates the overall amount of pruning needed to balance shoot growth with fruiting. (All this, and more, is detailed fruit by fruit in my book, THE PRUNING BOOK,). The younger the stems on which fruits are borne, the more stems need to be shortened. Peaches and nectarines, for instance, bear fruit only on stems that grew the previous season, so need fairly severe annual pruning to stimulate an annual flush of vigorous, new shoots for the following year’s crop. Prune enough so that a bird could cruise right through the branches without touching them.

Apple and pear trees, at the other extreme, bear fruit on long-lived, very short, knobby branches, called spurs, so need little such annual growth stimulus.

Young spur on older pear branch

Eventually, though, even spurs need pruning for rejuvenation and elbow room.

Thinning spurs on old apple branch

Most other fruit trees lie between the extremes of apples and peaches in bearing habit and severity of annual pruning needed.

I consider pruning satisfying and fun. If you don’t, no need to throw in the towel on growing fruit trees. Some fruit trees, such as American persimmon, pawpaw, juneberry, mulberry, and cornelian cherry, do fine with little or no pruning.

Szukis persimmon

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!