FORM & FUNCTION MEET WITH ESPALIER

Espalier Goals

Espalier (es-pal-YAY) is the training of a plant, usually a fruit plant, to an orderly, two-dimensional form. The word is derived from the Old French aspau, meaning a prop, and most espaliers must, in fact, be propped up with stakes or wires. This method of training and pruning plants had its formal beginnings in Europe in the 16th century, when fruit trees were trained on walls to take advantage of the strip of earth and extra warmth near those walls.

Espalier in Normandy, France

Why go to all the trouble of erecting a trellis and then having to pinch and snip a tree frequently to keep it in shape? Because a well-grown espalier represents a happy commingling of art and science, resulting in a plant that pleases eyes and, if a fruit plant, also palates. You apply this science artfully (or your art scientifically) with manipulations such as pulling exuberant stems downward to slow their growth, by cutting notches where stems threaten to remain bare, and by pruning back stems in summer to keep growth neat and fruitful.

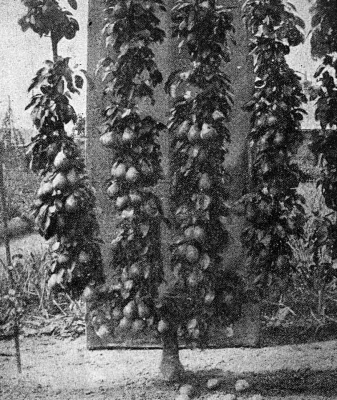

When all goes well, the tracery of stems on a fruiting espalier remains artfully in order year ‘round, and during the growing season each stem is clothed throughout its length with flowers and then fruits. Because the plant is bathing in abundant sunlight and air, the fruits are luscious, large, and full-colored.

Photo from old French book

Despite the constant attention demanded by an espalier, caring for it is not really a great hardship. The trees never grow large, so can be pruned, thinned, and harvested with your feet planted squarely on terra firma. And while pruning must be frequent, the cuts are small and quickly done, in many cases requiring nothing more than your thumbnail. And for some of us — me, for example — growing and maintaining espaliers is fun.

Plant Choices

In Europe, espalier is mostly applied to apple and pear trees. But the continental climate and daylength over most of the United States are very different from those of northern Europe, so the techniques applied to those plants here often fall short of expectations. Here, I’ve seen many espaliers with their branches shaped as desired but spotted only here and there with flowers or fruits.

Espaliers can be successful on this side of the “pond” by choosing the right kinds and varieties of fruits. In my experience, the best choices here for apples and pears are semi-dwarf Asian pears, columnar varieties of apples, and fully dwarf spur type apples or European pears. (Both dwarfing and semi-dwarfing trees are made by grafting stems of a desired variety of fruit on special rootstocks that not only restrict tree size, but also result in trees from which you get your first tastes of fruit sooner.)

Asian pear espalier

Red Currant, Training

Red currant is probably the easiest of all fruits to espalier. These espaliers also have the advantage of needing to be pruned only twice a year, in contrast to the monthly or more frequent pruning sessions apple or pear espaliers might need. And the fruits, dangling from the branches like translucent, red jewels, add much to the show. The espalier technique that I will describe can be applied as well to white currants (which differ in color but are essentially the same plants a red currants) and to gooseberries, close relatives of red currants with much the same growth and fruiting habit.

My red currant espaliers decorate the fence that encloses my vegetable garden. Each plant is trained to the shape of a T, with a single, upright, bare trunk capped by two fruiting arms that grow out in opposite directions along the fence. The fence itself provides support but wires and stakes could also keep the plant up.

Knowing a little about plant physiology helps in growing any espalier and makes doing so all the more interesting. Apical dominance, the tendency for the uppermost shoots on any plant to grow strongest, is one concept especially worth understanding. It results from hormones, produced in the growing tips of upright stems and at the high points of arching stems, which tend to suppress growth of other buds. Merely changing the orientation of a stem influences how strongly various parts of that stem grow, and growing stems might turn upward of their own accord in attempt to gain apical dominance over other stems.

In all plants, there is also an inverse relationship between stem fruitfulness and stem vigor. More vertically oriented stems are less fruitful and stronger growing, especially in their upper portions, than horizontal stems, which tend to be more fruitful, weaker growing, and more branched along their length.

I applied these concepts to my red currants right from the start. To develop a strong trunk initially, I chose the strongest shoot on my new plant, removed all others, and then tied that retained shoot to the fence to keep it upright and vigorous.

Once this trunk-to-be grew just above the top of the three foot high fence, it was time to develop the side arms. Cutting the top bud back to the height of the fence released the remaining buds from the suppressing effect of apical dominance. I selected two shoots that started to grow from the upper portion of the trunk to become fruiting arms, training them along the fence in opposite directions and removing all others.

To keep these developing arms growing vigorously, I left their ends free as I tied portions closest to the trunk to a horizontal position. The free ends did what they were naturally inclined to do, that is, turn upwards, and that upward orientation maintained strong growth from their ends. As the shoots lengthened, I kept tying down the older portions.

Red Currant, Maintenance

Maintenance pruning and fruiting began even as arms were developing. The arms, because of their horizontal orientation exhibit little apical dominance so side branches develop freely. This is good, because that’s where we hang the fruits. However, we can’t have those branches growing too long or else they’ll ruin the crisp T form of the espalier.

Two simple cuts keep the form neat while encouraging abundant fruit production. The first cut is made in summer just as the first berries show the slightest hint of color change. This cut entails nothing more than shortening every branch growing off the arms to about five inches in length. No need to be overly precise about where to make this pruning cut.

The second set of annual cuts takes place while the plant is dormant and leafless, sometime between midwinter and when growth begins in spring. At this time, I go over the plants, shortening all those five-inch-long branches again, this time to about one inch.

The plant will occasionally sprout new shoots either at ground level or along the trunk. These sprouts are removed whenever noticed.

Two cuts: That’s all the pruning a red currant espalier requires. The result is a plant that is as attractive as it is fruitful. The only problem I have with my red currant espaliers, which hang onto their berried treasures for weeks, is picking the fruits. I hate to ruin the plants’ appearance.

(Creating and maintaining an apple or pear espalier is somewhat different than doing so with red currant, and very different from doing so with peach, plum, fig, or a number of other fruits. If this topic interests you, I devote a chapter to espalier, covering a number of fruits and techniques, in my book, The Pruning Book.)

This is a very good explanation of pruning a currant espalier. I bought your pruning book when we were planning a small apple espalier at the community garden where I volunteer. Your pruning book is one of the best I’ve come across. You provide information about plant growth & fruiting, and therefore the principles that govern pruning choices. The one complaint I have about your book is the small gray text on gray and green background makes it difficult to read for those of us with weaker eyes. Next edition please provide more contrast between text and page.

Glad the book is helpful. I will keep your comment about text visual clarity when it comes time for a new edition. Thanks.

I was inspired by you to espalier my Zestar and Williams Pride apple trees about 13 years ago. They are beautiful and productive.

Two years ago a juvenile delinquent brown bear decided to try his hand at pruning but I was able to chase him off before things got too bad.

The trees have a few ‘war wounds’ but still produce great.

Nice work with the trees and the bear!

I love the look of the espaliered currants! Do you think they would grow well in semi-shade, under the canopy of an old oak? I have a vegetable garden set up, and the east side of the garden is in the shade of a tall oak, so I worry it’s not enough sun for an apple or pear, but maybe the currants would work? I’m off to buy The Pruning Book now, thank you!

Yes, currants do veery well in some shade, even better than in the sun in hot summer climates.