Three Fermentations

Here it is, 9:10 am in the morning, and I already feel very accomplished. Three fermentations are well under way. It’s fun and tasty working with our microbial friends.

The fun began last night when I scooped out a half a soup spoon’s worth of sourdough starter from a jar in the refrigerator to add to a mix of 3 cups of whole wheat flour, one and a quarter cups of water, and 1/8 cup of maple syrup. That sourdough starter is in its third year — here, at least. I carried it, dried, on a paper towel, back from Alaska, a gift from a friend there who said its caretaker’s ancestry traces back at least 100 years to . . . was it governor or captain someone? I’ve kept the starter refreshed by stirring a teaspoonful of it every week or two with an eighth cup each of flour and water, and incubating it. The microbial population, a mix of various species of Lactobacillus bacteria and Saccharomyces yeast fungi, has no doubt shifted under my care; whatever the present population, it makes fine loaves of bread.

Back to the bread . . . I mix it in a breadmaker or by hand for a minute or so, incubate it 12 to 18 hours (depending on the temperature), dust it with flour and give it two light folds, let it rise again for a couple of hours, and then throw it (almost literally, and the hardest part) into a pre-heated baking dish from a 450° oven. Into the oven it goes: thirty minutes covered, 15 minutes uncovered, and voilá. Delicious, hearty, fragrant bread.

What’s this got to do with gardening? I wish I could report that I grew the wheat. I tried, last summer. Yields were lower than expected, exacerbated in part by difficulty in threshing it. Kernels were reluctant to part with seedheads despite severe batting of the heads in a pillowcase. I’ll try again, and hope to grow at least enough for one loaf of bread.

————————————————–

One of my sourdough yeasts, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, was invited to my second fermentation, the preparations for which began much earlier this morning. Actually, this second yeast was more probably a relative of the sourdough yeast, a different strain or species, one best suited to fermenting malt syrup into alcohol. The finished product, in this case, will be beer. Saccharomyces cerevisiae came in a sealed packet from a store although beers have been made by mere capture of wild yeasts floating around in the air.

The first step in my brewing was to boil malt extract with hops. I have grown barley, from which malt can be made. Note the “can be;” my barley crop of last year is still hanging, stems and all, from a kitchen rafter. I bought the malt extract rather than go through the threshing, sprouting, toasting, cracking, and sparging steps needed to extract malt from barley. Hops is easier; all you need is the dried seed heads. I grow hops, a decorative and fragrant plant, which is all my young plant is thus far. I also bought hops.

I did go out to the garden after the 45 minute boil to gather black currant leaves and clove currant fruits. These two aromatic plants, steeped along with more hops in the cooling malt-hop mix, will add a subtle and unique flavor to the batch of beer.

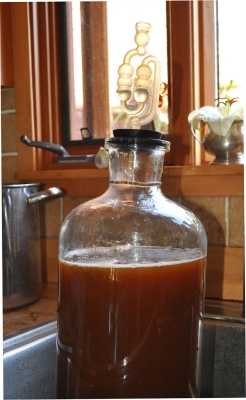

Once diluted to 2 gallons, poured into a glass carboy, and cooled, the mix was spiked with the yeast. An airlock tube with water in it lets carbon dioxide exit without letting air in.

It’s now 1:30 pm in the afternoon, and already bubbling noises from the airlock offer evidence that the Saccharomyces are happily at work. Well, not working, just eating. In two weeks, they will have digested all they can and the brew will be ready for bottling.

———————————————-

Around here, compost-making — the third fermentation du jour, is always in progress. Composting is perhaps the most complicated and the easiest of all the fermentations.

This evening, I plan to get some manure to feed the panoply of microbes that call the compost piles home. Not that manure is necessary for making good compost. Basically, all that’s needed is any organic material, which is anything that is or was living. Microbes in my piles have been eating old lettuce plants, pulled weeds, banana and orange peels from the kitchen, some coarse, weedy hay I cut with my scythe, and occasional sprinklings of ground limestone, kelp, and soil.

Fermentation in the compost differs from that in sourdough bread and beer in that conditions and foodstuffs are always changing. If I add a bunch of material at once, temperatures within the pile rise rapidly, up to about 150° F. Different kinds of fungi, bacteria, and actinomycetes become prominent within different temperature ranges. Also, different microbes become dominant depending on what foods I add to the pile and their stages of decomposition. For instance, old cornstalks are rich in lignin, which only certain fungi can use as food; once the fungi have gone to work on that lignin, certain bacteria might move in to work on byproducts, which include dead fungi.

Compost happens quickest when just the right balance of food, moisture, and air exist within a pile. The nice thing about making compost, though, is that whatever goes into the pile eventually becomes compost no matter what the foodstuffs or conditions. Sooner or later, compost happens

Compost is not, of course, for eating, but spread on the soil makes for some mighty tasty fruits and vegetables.

————————————–

The fun part of working with these microbes is not only the tasty products that result, but the congenial blend of art and science that get you there.