Disease & Smelly Plants

You perhaps missed last summer’s plant plague, which might be back this summer. My garden was spared because last summer I happened not to have planted the particular host plant: impatiens (Impatiens walleriana), that workhorse of the shade garden, one of the few brightly colored flowers that thrive with little sunlight.

Downy mildew disease was the cause of last summer’s plague, which descended on impatiens throughout much of the northeast and parts of the rest of the country. Leaves of infected plants turn pale green at first, then develop downy, white growth on their undersides, and finally collapse. Stems also can eventually pick up infection. Needless to say, infected plants flower little or not at all.

|

| Impatiens in Puerto Rico rainforest, El Yunque |

But let’s look forward rather than wallowing in the past. Downy mildew can be expected this year wherever it reared its ugly head last year. Same goes for next year, and the year after, and . . . the spores survive for years in the soil. Downy mildew might even show up where it wasn’t last year, coming in on infected seedlings (early stages of infection are not very obvious) or on spores which, under good conditions, can travel hundreds of miles.

Downy mildew thrives under cool, wet conditions, so the very least that can be done would be to keep fingers crossed and hope for the best. Even better: avoid watering impatiens late in the day or in the evening, and thoroughly clean up everything at the end of the season. Better still: Grow your own plants from seed and/or grow New Guinea impatiens (I. hawkeri), a resistant species parading under such trade names as Fanfare, Divine, Celebration, Celebrette, and Sunpatiens.

The surest bet against downy mildew of impatiens is to not grow the plant. Not being able to grow brightly colored flowers in the shade need not leaves these areas dark and lugubrious. Consider plants with brightly colored leaves, such as caladium, begonia (which also has flowers), and coleus.

By the way, impatiens downy mildew is caused by a different organism than the ones that cause downy mildew on sunflowers, zinnias, and some other plants, so no need to worry about the disease spreading from or to these plants.

——————————————————–

P.U.! What an olfactory “good morning” from amorphophallus, about which I wrote a few weeks ago. At that time, a flower stalk was pushing forth from the top of the bare bulb sitting, soil-less, on a plate. Today, the stalk, 18 inches from tip to toe, finally unfolded its skirt-like spathe up the center of which rose the long, fleshy spadix on which the tiny flowers sit. The whole thing is very eerie and interesting but not particularly pretty.

Having grown the plant decades ago, I knew what to expect, nose-wise, from the plant in flower. So I’ve kept a close eye on it and today my nose trumped my eyes. My remembrance was the plant having the aroma of rotting meat. Todays flower was more reminiscent of a horse barn, but perhaps the plant was just gearing up for its full olfactory show. I took some quick photos, then lopped off the flower stalk and tossed it out the back door. Even my dog Scooter showed little interest in the smelly stalk, the aroma of which is meant to attract carrion insects.

|

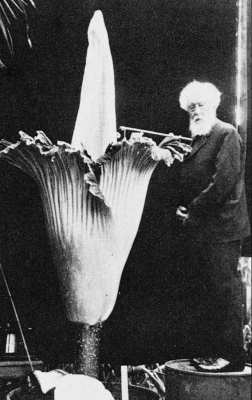

| Hugo de Vries and amorphophallus, 1937 |

About 200 species exist of Amorphophallus, the largest being A. titanum, whose flower stalk can soar to 8 feet high and whose spathe is the size of a small bathtub. This species caused quite a stir back in 1937 when a bulb at the New York Botanical Garden, after growing only leaves for a few years, finally flowered. A photo in the New York Times showed the great botanist Hugo de Vries perched next to the enormous flower. How did he stand the smell?

————————————————————–

Anyone who thinks gardening is tough, what with weeds, insect pests, and diseases, should feel for the Helvenstons, who garden in Orlando, Florida. Not that they have more pests there than we have here, but they have a different kind of pest, city ordinances. Orlando’s ordinances dictate sizes (25% of front yard area), heights, setbacks, and other aesthetics of front yard vegetable gardens but nothing — and here’s the clincher — about water or pesticide use, both of which have environmental repercussions. The Helvenstons’ vegetable garden takes up — no, makes optimum use of — their whole front yard.

If the Helvenstons fail to comply with the ordinances, which at present are recommendations and have to go to the city council for vote, they could face fines of $500 per day. “Our Patriot Garden pays for all of its costs in healthy food and lifestyle while having the lowest possible carbon footprint. It supplies valuable food while being attractive”, says Jason Helvenston. “They will take our house before they take our Patriot Garden.”

The fight for the right to grow vegetables — or lawn or ornamentals or whatever you want — on your own property has gone national. To join the fight, or for more information, visit the website www.patriot-gardens.com.