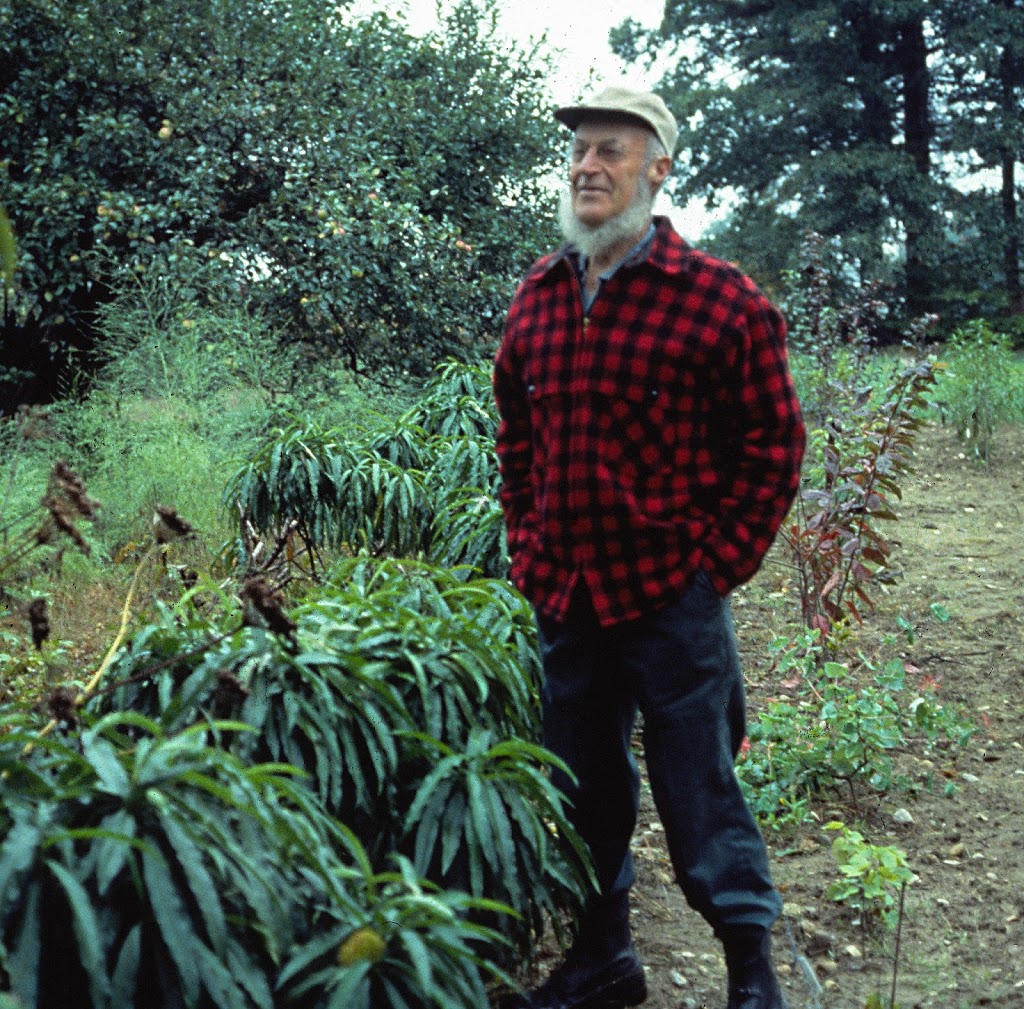

“It takes a patient man to net an acre of blueberries.” The New England accent added weight to the declaration, as did the gentleman’s 80-something year old frame standing ramrod-straight and adorned with checkered jacket, a cap, and chinstrap beard. That was 30 years ago, and I was standing in the New Hampshire garden of Elwyn Meader, looking across the field at his acre of blueberries. Elwyn was a plant

breeder extraordinaire, then retired, who had developed new varieties of such plants as persimmons, chestnuts, lilacs, cucumbers, soybeans, watermelons, and everbearing strawberries. The honey-sweet Fallgold raspberry, my favorite, was Elwyn’s handiwork, incorporating genes from Korean raspberries he found while working there for the U. S. Army.

Now, many years later, I think of Elwyn’s words as Deb and I rush to net our small plot, two-hundredths of an acre, of blueberries. (Not so small, though, to obviate a very respectable harvest of about 190 quarts of delectable, organic, sustainable, artisanal berries from 16 plants!) I append Elwyn’s words with “Covering two-hundredths of an acre of blueberries is a test of a marriage.” Nets can sag; tempers can thin; ladders can become unwieldy.

We survived. My latest incarnation of blueberry protection against birds starts with an enclosure of locust posts about 8 feet apart, with rebar running through holes a few inches from their tops. The sides, as my friend Bill calls it, my “Blueberry Temple,” are enclosed permanently in heavy duty, plastic bird netting (www.bennersgardens.com). Eighteen-inch-high chicken wire at the bottom keeps rabbits from chewing through the plastic.

Now for the seasonal net, the one that tests our marriage and covers the planting while berries are

ripening, from late June until September. This net is of woven nylon, so is sturdy and drapes well (available from such sources as www.raintreenursery.com, www.jacissel.net, www.nylonnet.com). We spread the rolled up net on the ground near the entrance to the planting, then, each of us climbing a ladder at either side, lifts the roll up across the top, with either end of the roll resting on opposite sides of the rebar. Letting the free end drape a little over the entrance side, we each use a binder clip to fix the beginning of the roll near the entrance side. From then on, it’s a matter of unrolling the netting over the top, clipping and moving ladders as we go and — this is the part

that can get testy — making sure to keep the net even on both sides and sufficiently taught.

This year, the net was up in less than a half-hour, the blueberries were safe from birds, and the marriage was still intact.

——————————————

Pruning tomatoes is such a pleasant garden “chore.” As I look over each plant for suckers — any shoot that originates at the upper part of juncture between a leaf and main stem — I get to monitor the swelling fruits, do a health check on the leaves and stems, and admire the plants’ neat growth habit. The latter comes from my weekly pruning off of the suckers followed by tying of the main stems to adjacent bamboo poles.

I can appreciate disorder in the garden but I also appreciate order. Disorder lends a pleasant, loosey-goosey atmosphere to the landscape. I find order more calming and an easier environment in which to satisfy the needs of each plant. For the tomatoes, pruning and staking them — which surely puts them in order — also gives greater yields (per square foot of garden space), and fruits that are cleaner and a bit earlier.

All this orderliness crumbles as August fades into September. By then, errant suckers get the best of me and the ever-elongating main stems reach the tops of their bamboo supports. Then where can they go? Sideways? Down? To an adjacent pole? No matter. By then, the end of tomato season is in sight and the plants pretty much do what they will as long as they keep pumping out juicy, red orbs.

——————————————

The novelty of cicadas has worn thin. Their electronic cacophony whines in various pitches throughout the day without a moment’s respite. If you saw me walking past any one of my many infested trees or shrubs, you might see my arms flailing about to keep airborne ones at bay.

Thankfully, cicadas aren’t feeding on any plants. But their egg laying, beneath slits they make in bark, can cause damage. Young stems dying back do little damage to established trees and shrubs (gratuitous summer pruning of shoots?), but can kill young plants.

Here, the cicadas favor the lilac bush and pear trees and, to a lesser extent, the apple trees. I’ve gotten pretty good at snatching them by their wings. My chickens are very fond of the fresh, less so the frozen, catch of the day. This hand to hand combat feels good but makes but a small dent in the population.

The other afternoon I could no longer stand the sight of so many cicadas clustered on the trunks of my 8-year-old pear trees. I needed a bulk method, so ran indoors to grab a dust broom. The dust broom was quite effective, sending cicadas flying everywhere. And then back onto the trunks.

My last resort was to get out my sprayer and coat the trees and any resident cicadas with ‘Surround’, a commercially available,

organically approved pesticide made from kaolin clay. The coating makes for unpleasant footing and egg-laying for a variety of insects, and it clogs their spiracles.

The ‘Surround’, which I applied only to the apples and pears, had but little effect on the cicadas. Cicadas on plants became statuesque; a few fewer flew back on, for awhile. Of course, the incessant cacophony emanating from the woods continued. Only a couple of weeks or so to go, and then a 17 year hiatus.